What do in-vitro human skin, spider silk and cow manure have in common? They are all unlikely materials that can cloth, protect and inspire humans, as realized by award-winning designer Jalila Essaïdi.

Her transdisciplinary work, in which creativity meets scientific exploration, unlocks the potential of weird and wonderful biomaterials to address relevant social and environmental issues.

Essaïdi succeeds in transforming our view of the natural world, by going beyond an aesthetic admiration of nature and challenging us to reconsider the amazing capabilities of less marketable, overlooked and often undesired bioproducts.

As a resistor of labels, her work is interdisciplinary, and seeks to see design ‘problems’ as opportunities for change. She is specialized in the fields of bio-based materials and biological art (bio-art).

With the Dutch Design Week 2019 just around the corner, we caught up with Essaïdi to discuss her vision on design, how biomimicry informs her work, and her appointment as an ambassador for the leading design event in Northern Europe. But first, let's get you acquainted with her work.

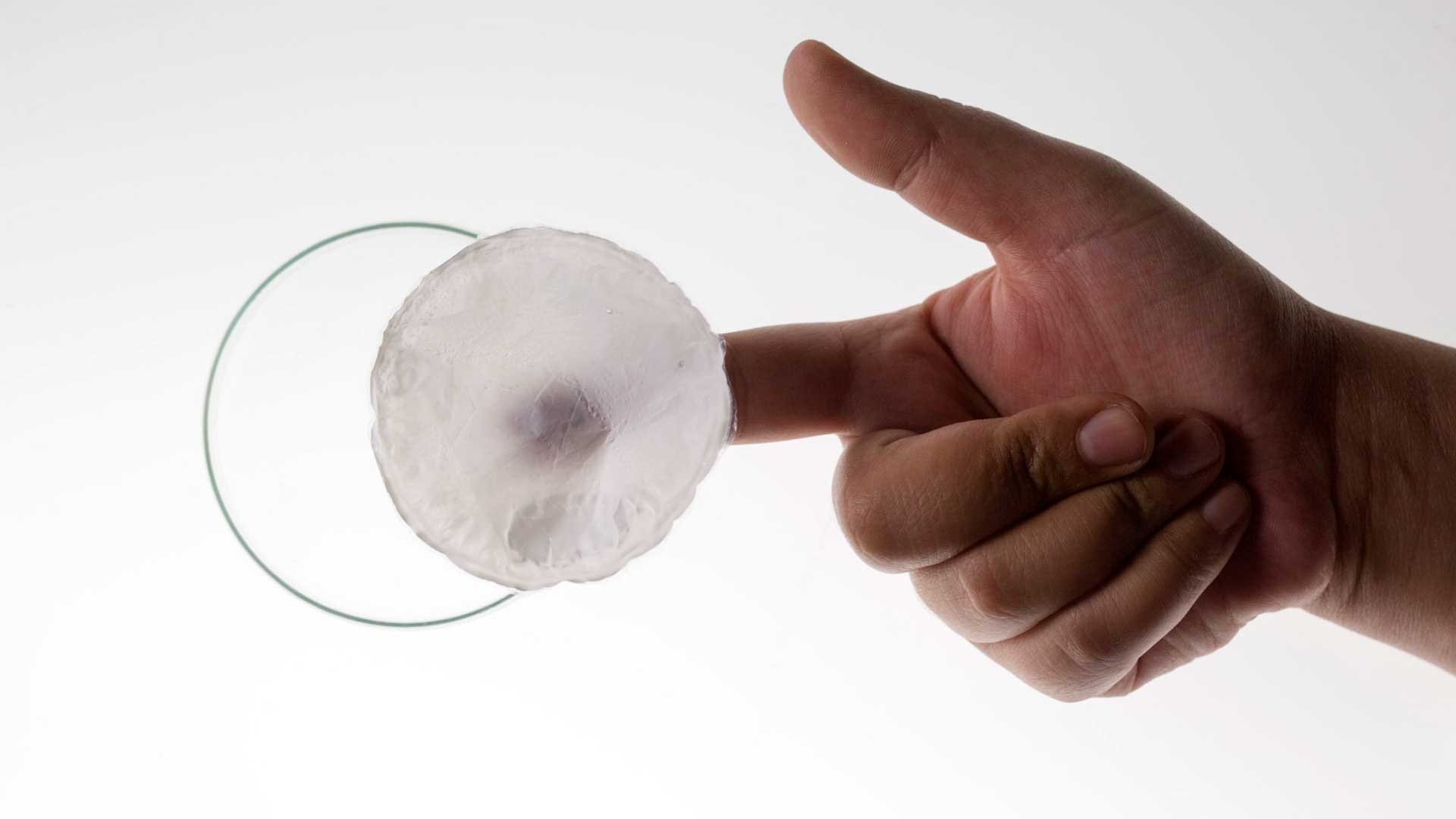

Bullet-proof skin

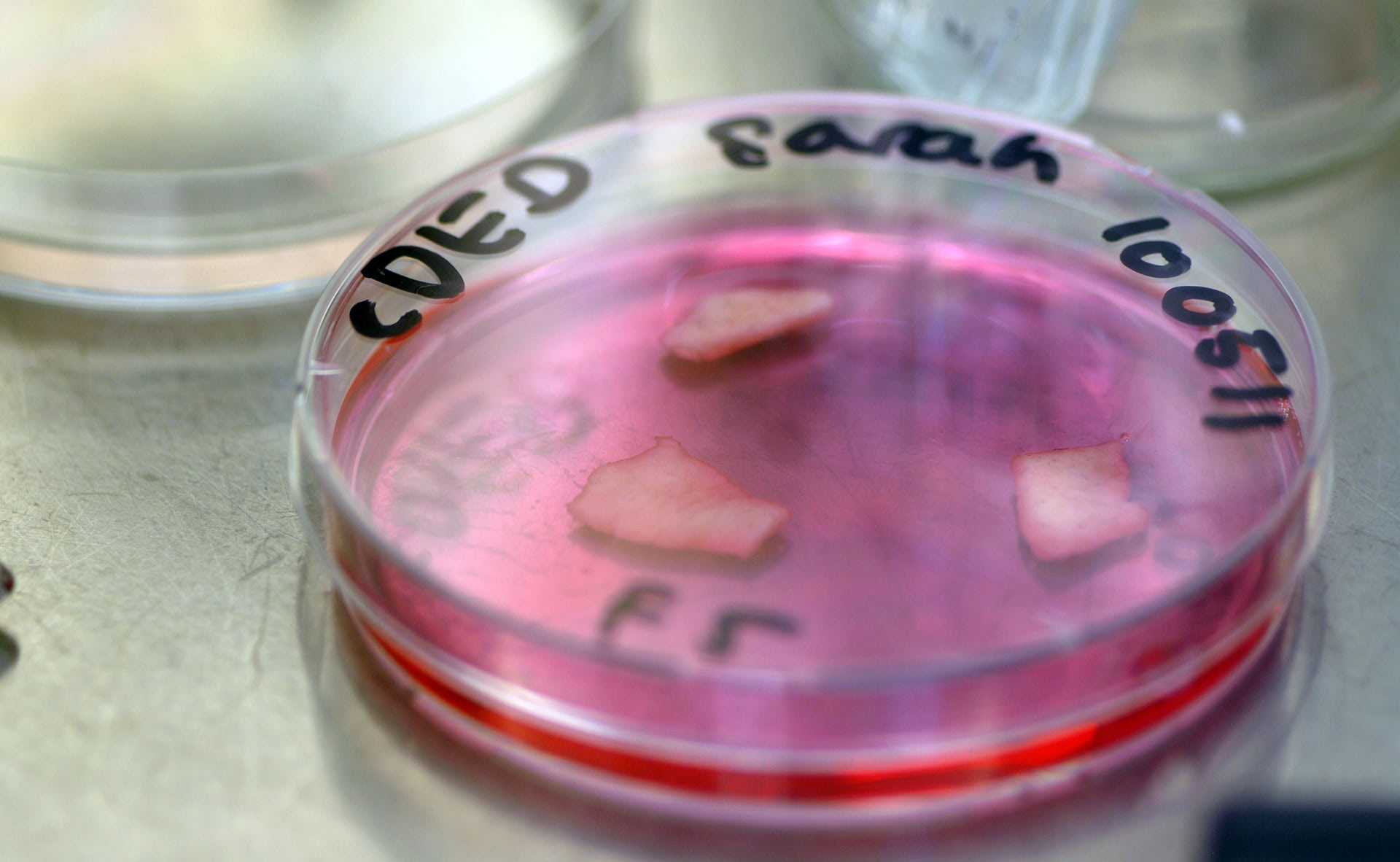

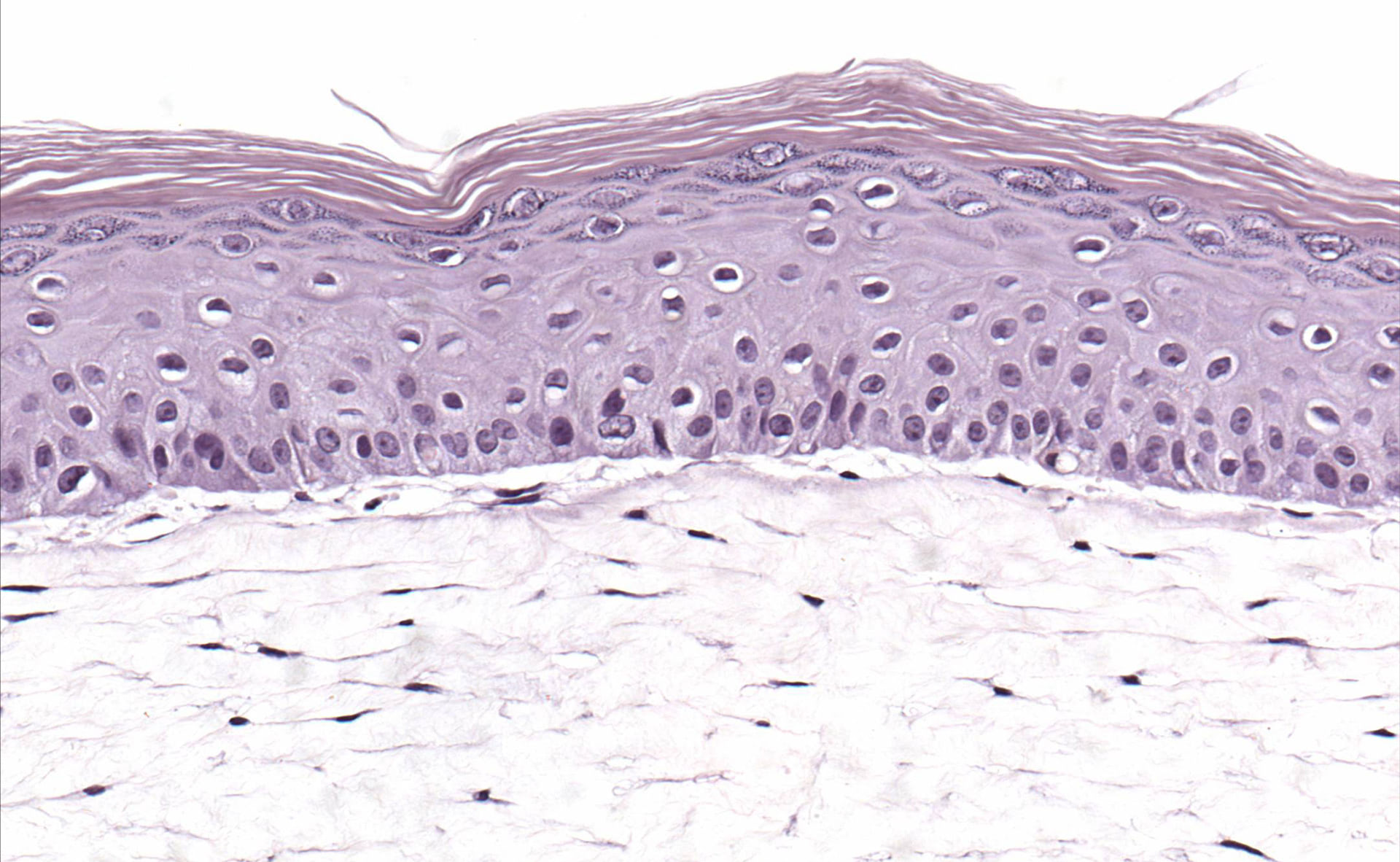

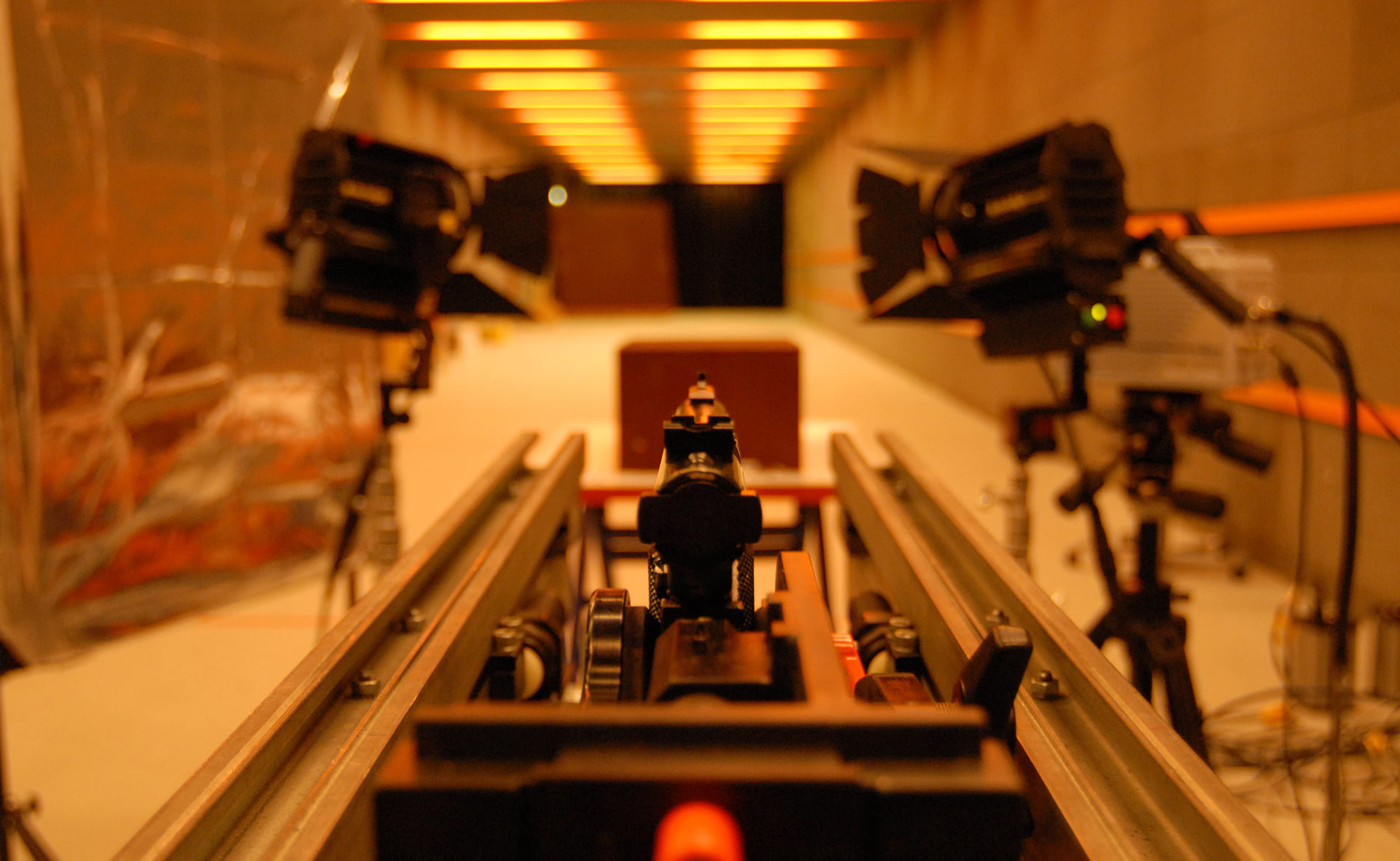

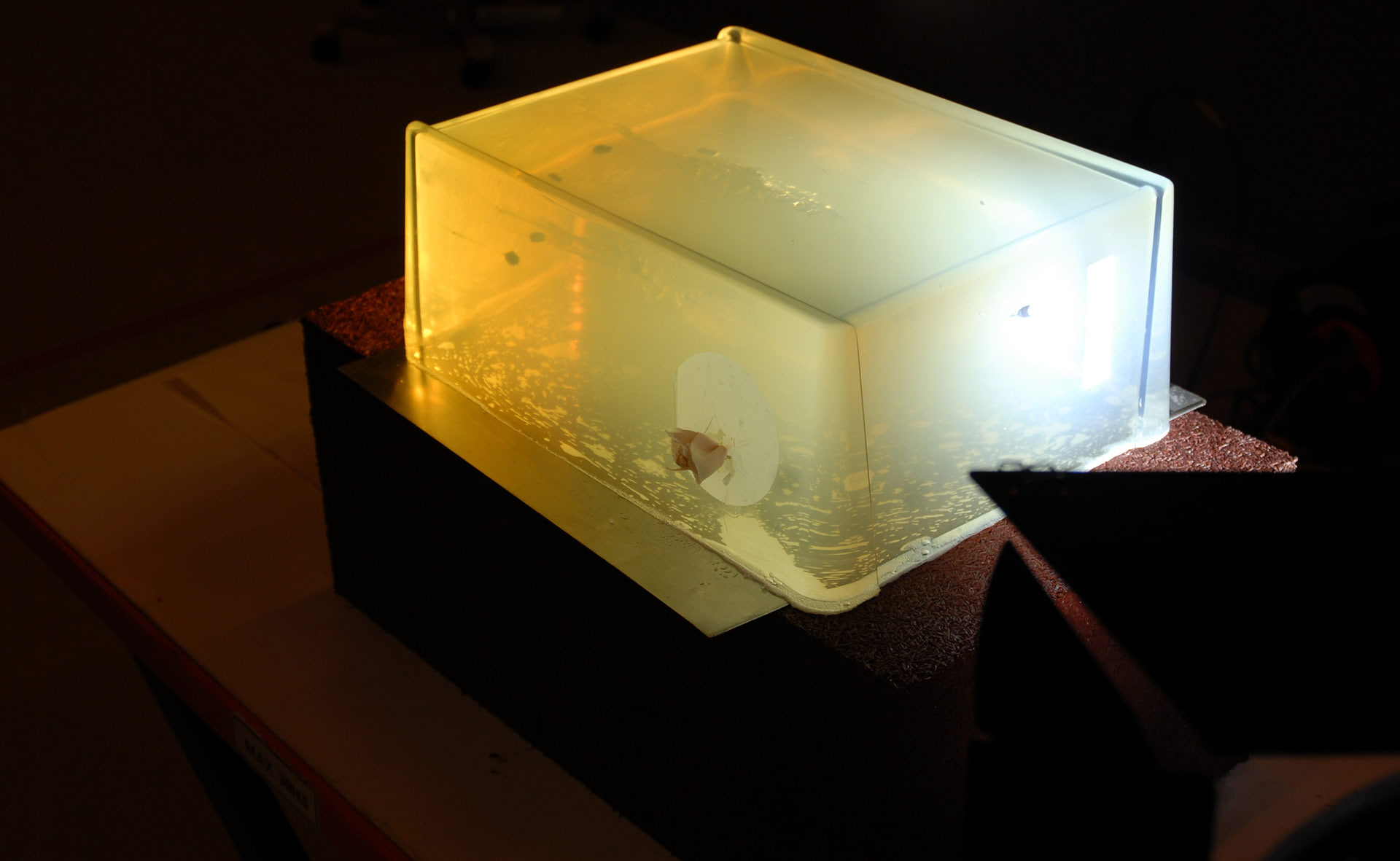

For one of her infamous projects, Bulletproof Skin’ or ‘2.6g 329m/s, Essaïdi combined in-vitro human skin with spider silk from genetically modified goats. Seems incomprehensible, right? Wrong!

Essaïdi delivered proof of concept in the form of a bioengineered human skin capable of stopping a low-speed bullet. The project received the Designers & Artists 4 Genomics Award in 2010, which offers funding and support to designers and artists who collaborate with life sciences to produce groundbreaking, interdisciplinary works.

To give you an idea of how it works:

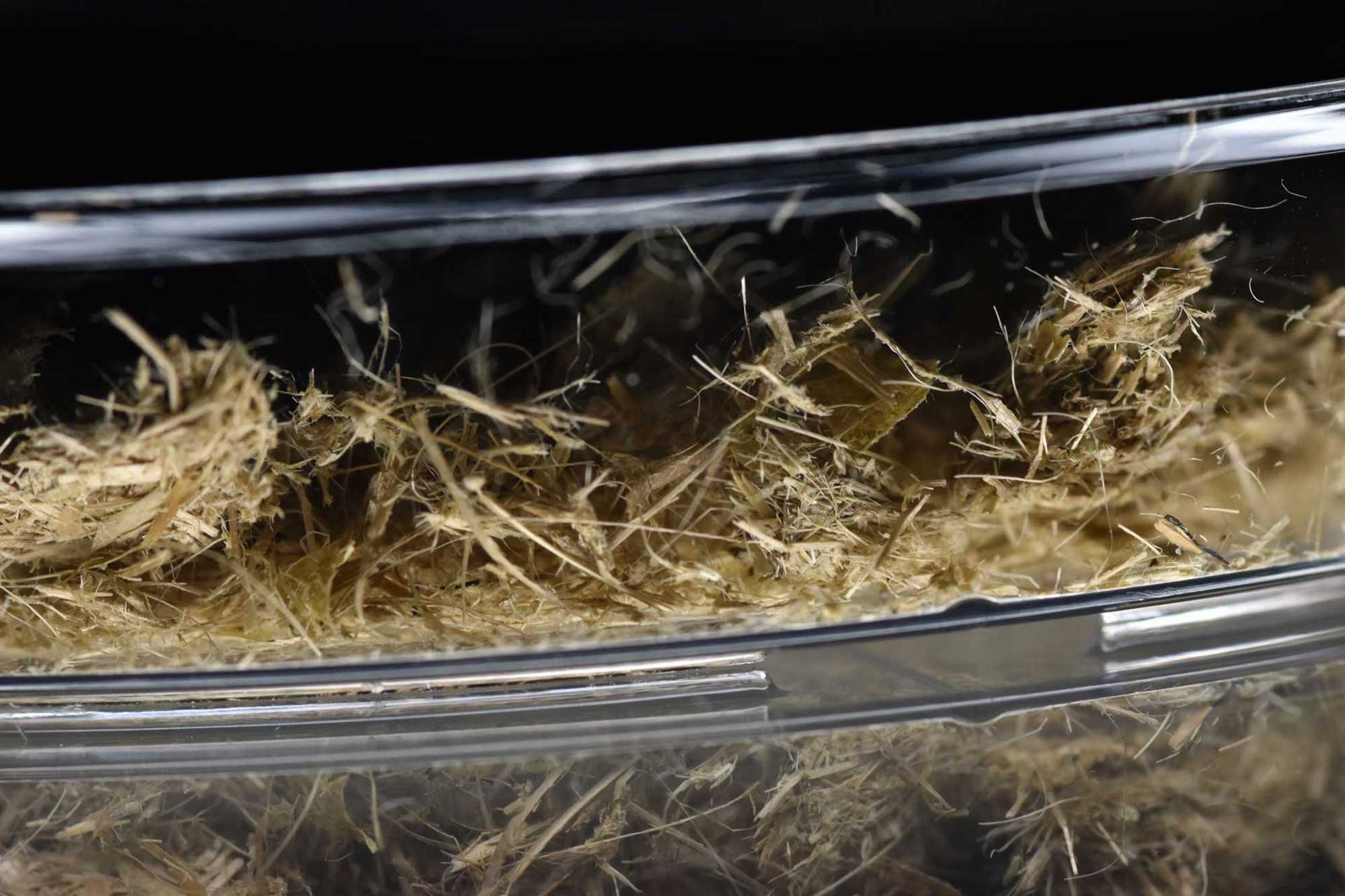

Cow-manure couture

For her project Mestic, Essaïdi transformed cow manure into cellulose-derivatives. With this venture came the possibility of forming a local, manure-based economy. By using excess manure for the production of plastics and textiles, this project revolutionized the way we look at waste.

"In nature nothing is considered waste. Yet manure, in its essence, is easily considered the most vile substance we know. Mestic shows that even this most disgusting matter is inherently beautiful."

Behind the materials

While the above designs are characterized by the use of unconventional materials, Essaïdi’s works always go deeper to address wider issues.

Bulletproof Skin, for example, is about the relativity and dual nature of security. The work forms a response to the culture of fear that has emerged from news feeds and social media channels that manipulate our feelings of safety.

Additionally, Mestic strikes at the heart of our aversion to waste by demonstrating how even the ‘disgusting’ can be inherently beautiful. Essaïdi shared her approach, stating that "the materials are results, they enable me to tell the story." And, when it comes to materials she would like to work with in the future, she sees no boundaries: "none of them are off-limits."

"The materials are results, they enable me to tell the story."

Besides her artistic practice, Essaïdi is CEO of Inspidere B. V., a biotech company to envision, develop, design and implement sustainable new materials and products, and accelerate their path to market.

She also founded the BioArt Laboratories. Here, she welcomes scientists and designers from all over the world to collaborate on projects that push the boundaries of art, design, technology and science. The BioArt Laboratories offer participants "the right tools and critical questions to help steer their work and overcome obstacles", and in turn, those who take part "bring various perspectives on nature and technology." Projects have varied from exploring desert animal adaptations as a solution for drought, to converting food waste into textiles as a way of challenging consumption habits.

Given that her work champions ‘innovation inspired by nature’, Essaïdi elaborated on how sees the relationship between humans, nature and technology in design: "There are many elements of nature that we can learn from, or ideas that we can ‘steal’ or adapt into technology in a sustainable, non-invasive way."

Indeed, her approach is characterized by respect and admiration for nature, and she further believes that through studying natural processes we can find solutions for contemporary issues. She highlights that "by looking at nature’s adaptations to environmental changes, humans can learn how to use technology to adapt to societal changes as well."

"By looking at nature’s adaptations to environmental changes, humans can learn how to use technology to adapt to societal changes as well."

Here we see how biomimicry plays a role in Essaïdi’s philosophy as an artist. By exploring the composition, processes and capabilities of natural materials, she demonstrates the exciting possibilities that emerge when we decenter the human and allow nature to become our mentor. Work of this kind can allow us to think of nature as a resource to be collaborated with rather than controlled.

What will Essaïdi bring as DDW ambassador?

Moving on to Essaïdi’s appointment as DDW ambassador, we were curious to learn what she wanted to bring to her role this year. Her answer is clear and concise: "I have always been interested in design projects that offer more than just economic value. As an ambassador, I want to raise awareness of different values that design can offer, such as ecological gains and sustainable applications."

Essaïdi further agreed that her appointment may represent a shift in what is expected from design and its future possibilities: "I think my goals fit a larger trend towards global awareness of the importance and urgency of sustainable design."

"I want to raise awareness of different values that design can offer, such as ecological gains and sustainable applications."

Indeed, this year’s DDW theme, If Not Now, Then When?, seems to support this sense of urgency, and has been described in the press as a ‘call to arms’. Asking Essaïdi whether design had reached its potential as a tool for change, she crucially pointed out that "humans have been constructing the world to meet their needs by design for eons."

"It is not so much the question if design has reached its potential as a tool for change, but if we are willing to explore and understand evolving and complex problems and turn them into sustainable solutions. The tools are there, we just need more problem loving creative change-makers."

"The tools are there, we just need more problem loving creative change-makers."

So, where can we find these problem loving creative change-makers? Essaïdi highlights the importance of experimental spaces like the BioArt Laboratories in working to meet this urgent need. She sees the initiative as an essential, collaborative "movement of creative change-makers — willing to reconfigure our current practices towards a circular economy."

We are excited to have Jalila Essaïdi on board as a speaker during the DDW Talks: Bio Design. Note: This event is part of the professionals program (register for early bird €75 via this link). But members of Next Nature Network attend this event for free! Drop us a line to claim your ticket.

Share your thoughts and join the technology debate!

Be the first to comment