Japanese researchers are currently working on cloning a mammoth, and plan to produce a fluffy new prehistoric calf within four or five years. The bucardo, an extinct subspecies of the Spanish ibex, was resurrected for a few minutes in 2009 before the clone died. 'Frozen zoos' now keep the cryo-preserved tissues from dozens of endangered species to hedge their bets against future extinction.

Until we have the godlike knowledge to reconstruct a genome from the base pairs on up, our resurrected zoo will be limited to the animals that we have stored away for safe keeping. Sorry, no dinosaurs, but there are at least 500 stuffed and dried passenger pigeons, 731 thylacines, and one remaining dodo specimen with soft tissue remaining.

These numbers are misleading-- so far, scientists have only been able to clone long-gone animals from frozen tissue. The pool of acceptable candidates for cloning for any extinct species is therefore vanishingly small. Except in the case of creatures that were lucky enough to make it into San Diego's Frozen Zoo, scientists may be able to resurrect only one or two unique individuals from any species.

The meaning of 'extinction' will be radically redefined when, and if, an extinct species is successfully revived from preserved tissues. It's likely that we may see a healthy cloned Pyrenean Ibex in the near future, but it would only ever be that one bucardo, repeated over and over again from the individual knocked out by a falling tree. When the clone dies, the species will go extinct again, and when it is cloned again, it will be resurrected again, periodically cycling through extinction and resurrection. Zoos and collectors might request their own bucardo, mammoth or lonely dodo to put on display - all the same individual.

The same species would exist in the shady realm between real and imaginative. The "species" for these one-off clones would no longer be a biological category, but a cultural one. It would be a product of human imagination and expectation, a virtual concept of "species" that is embodied briefly in one organism. If, for instance, parental care, social interaction, and ancestral memory of migration routes and mating grounds are necessary to say, make a mammoth an authentic mammoth, then a single clone would not qualify as anything more than a very convincing fake.

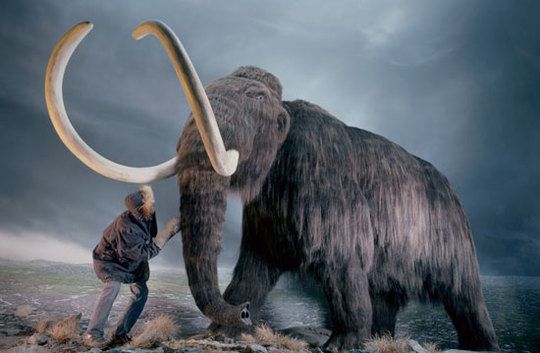

Image via Science Ray.

Allison Guy

Of course, the "will of nature" is an entirely subjective thing. Humans were directly responsible for the extinction of dodos, thylacines, and passenger pigeons. The best evidence indicates that early human hunters were also responsible for the extinction of megafauna such as mammoths, wooly rhinos, giant ground sloths, and so on. Bringing back these species is not going against some natural trend, but atoning for human error.

Posted on

Troy Sharpe

interesting as a scientific study but these species have already gone extinct. to bring them back would be going directly against the will of the nature, a world in which these animals had their chance and did not survive. to clone them would have no better purpose than a zoo would. even less so perhaps as zoos can have catch and release programs and educational elements for conservation and awareness.

Posted on

Allison Guy

Emma Marris recently wrote a more nuts-and-bolts article on the difficulty of cloning extinct species: no species-specific gut flora, no parents, and no ecosystem. Interesting read. http://www.lastwordonnothing.com/2011/09/26/guest-post-should-we-clone-endangered-species/#more-2635

Posted on

Koert van Mensvoort

Nice example of post-linear, post-historic database culture. I thinks it was philosopher Jos the Mul who said: "For someone whose main instrument is a computer, the world becomes a gigantic database."

Posted on