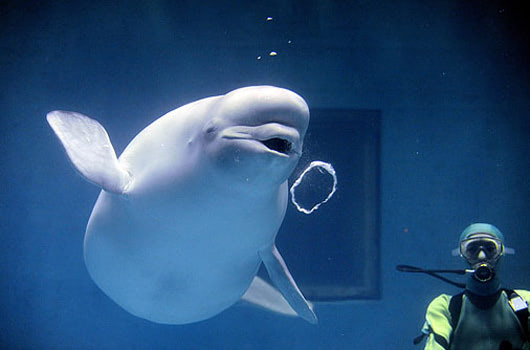

An ingenious Russian crow that used a lid as a snowboard to slide down a snowy roof persuaded millions of YouTube viewers that animals are not merely beasts of burden – they also want to have fun. Indeed, the natural world appears to be teeming with creatures enjoying themselves in all kinds of different ways, and wildlife experts even claim that bonobos and dolphins have sex for fun.

But how can we know this is the case? Aren’t we really just projecting our human values on to animals? After all, moods are subjective, so it’s hard enough for humans to communicate clearly enough to each other, even when they share the same language – let alone try to figure out what another species might be feeling. So, to keep things simple and empirically testable, the kinds of scientific experiments that have established the ‘feelings’ of animals have focused on responses to stimuli in which cause and effect are not at all complicated such as withdrawal from pain [1].

Unsurprisingly, this has produced a very limited model of scientifically ‘proven’ animal behaviour, since there are still no clearly identifiable behavioural markers of conscious experience that don’t involve language. We still don’t know how to unequivocally prove what animals may be thinking. We can only claim that creatures such as these fox cubs playing on a trampoline appear to be having fun, since we cannot be objective about what we observe. However, the work of philosophers of science such as Thomas Kuhn, Stephen Toulmin and Patrick Heelan, among many others, questions the long-held view that scientific data are absolutely objective.

Perhaps there is room for subjectivity, or other qualities not traditionally explored by science, which may provide useful insights into the way that nature works. D’Arcy Thompson noted the effusive ability of nature to make patterns [2] and thought of biological form as the consequence of relentless, dynamic forces that are shaped by flows of energy and stages of growth without a pre-determined purpose. The appreciation of nature’s creative qualities, rather than its traditionally accepted functional diligence, suggests that there may be a frivolous, even excessive side to nature. This is lost when observations are reduced by the scientific method into discreet, measurable parts. Philosopher Dan O’Hara, who researches the drivers of novelty, proposes that invention is the mother of necessity, in other words, nature finds its own uses for things (William Gibson famously observed that ‘the street finds its own uses for things') [3].

So, if there is a more ‘playful’ side to nature, from pattern generation to animal behavior, then it is possible that creatures are able to benefit from the rich diversity of experiences that nature has to offer and are equipped with appropriate behaviours for discovery such as exploration and play. For example, magpies are notorious for collecting objects - not because they are choosing the best building materials to make a nest with, but simply because they like them.

Nobel Prize winner Ilya Prigogine offers a way forwards in articulating a more holistic, phenomenologically inclusive kind of science, which has been aspired to by thinkers such as Jan Christian Smuts, Vladimir Vernadsky, James Lovelock and Rupert Sheldrake. He proposes that the world is not simple or mechanical in its ordering, but complex and fundamentally creative. This science is still very young and controversial. It requires its own set of tools, methods and materials – to break free of the exclusive discourses of function and efficiency – before it can start to radically re-articulate our experience of the world. In the twenty-first century nature we are likely to see a re-characterization of nature as quintessentially creative, intrinsically playful and fun loving. These bountiful ideas will replace the rather puritanical, mechanistic model that we currently use and herald more ecologically compatible forms of human development. Perhaps some readers will already recognise these generous signatures – they are next nature.

Image of a beluga blowing a bubble ring via the Daily Telegraph.

References

1. Griffiths, D. P., Dickinson, A. & Clayton, N. S. (1999). Declarative and episodic memory: what can animals remember about their past? Trends Cogn. Sci. 3, 74-80.

2. Thompson, D W., 1992. On Growth and Form. Dover reprint of 1942 2nd ed. (1st ed., 1917).

3. Gibson, William (1981) Burning Chrome and Other Stories. London: HarperCollins. P 215.

Share your thoughts and join the technology debate!

Be the first to comment