It’s a cold and rainy day in Amsterdam. I am about to leave the house for a hunting and gathering session at the supermarket, a few hundred meters from where I live. Before leaving the house I take my smartphone out of my pocket. I open the shopping list app one more time, just to make sure I don’t forget anything. You can tell it’s a typical list of all the primary needs of an urbanite in his forties that calls himself a designer and doesn’t need to support a family:

- Espresso beans (organic, dark roast)

- Champagne/prosecco (1 bottle)

- Snacks (french cheese/charcuterie)

When I arrive at the supermarket I see a Tim standing in front of the entrance. He is there every day, ready to greet every new customer. He greets me with a smile as if it is a beautiful summer day. In his hands, a soaked copy of the magazine he sells. It’s one of those street newspapers that are produced and sold by homeless people like Tim, to help support themselves. I like the newspaper, and usually buy a copy. But I don’t have cash with me, so unfortunately I can’t buy one today.

This is not the first time I skipped buying from Tim. To be honest, it must have been months, if not years since the last time I bought one. The reason is quite banal; I never carry any cash anymore. I mean: who does these days? Most cash transactions have been replaced with card payments years ago, and currently cards are being replaced with payments by phone, which in return will likely get replaced by iris scans, in a not-too-distant future. I greet Tim politely when passing and feel a bit guilty for not buying the newspaper, so I quickly set my mind to foraging.

Privileged by Design

Twenty minutes later I arrive back home. I unpack my groceries with one hand, put the wine and prosciutto crudo I just bought in the fridge and look at the smartphone in my other hand. It looks like a miniature monolith made out of obsidian, a beautiful, almost magical object. One that connects me to a wealth of information and entertainment. It offers tools that make my life comfortable and frictionless. It is also a device that stands right between Tim and his potential to earn an income.

And together with Tim, there are millions of people in the world who cannot keep up with the high technological standards of the industrialized part of the world. I know this already, but my brief encounter with Tim today makes that I really feel it. It makes me reflect on my own privilege, which on the one hand is related to my socio-economic position, and on the other hand to the role technology plays in my life.

That evening, I open my laptop and start researching the topic; I read that The Cambridge English Dictionary describes privilege as the unearned (and mostly unacknowledged) societal advantage that a particular person or restricted group of people has beyond the advantages of most, usually because of their position or because they are rich. In social sciences, this special status or advantages is conferred on certain groups at the expense of other groups.

A few clicks further, I come across the essay ‘White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack’ (1989) from the social researcher Peggy McIntosh. In this essay, she describes privilege as ‘an invisible package of unearned assets which I can count on cashing in each day’. She continues to describe her privilege as ‘an invisible, weightless knapsack of special provisions, maps, passports, codebooks, visas, clothes, tools and blank checks’. Note that the metaphor she chooses is a set of technologies!

What if we would see technology through the lens of privilege?

And it is here, that something clicks with me. What if we would see technology through the lens of privilege? And what if we would borrow elements of Peggy McIntosh's approach in doing so? My experiences just an hour ago suddenly connect to memories of other events, especially those of the last 1,5 years that have been dominated by the global COVID-19 pandemic: the ease with which the university where I teach switched to remote teaching during the first lockdown in 2020 while it was clear that not all students had proper laptops or wifi at their student homes. Even in a wealthy country like The Netherlands. Or the vaccine wars, both on an interpersonal as well as on an international level. To me, one thing is clear: I need to check my Technology Privilege!

I want to paraphrase Peggy McIntosh: Technology Privilege is like a Swiss Army knife, or a smartphone for that matter, full of handy tools and applications that make your life safer, more comfortable, more enjoyable and maybe even more meaningful (depending on who you ask of course). Almost anywhere in the world, technological advancements are crucial to meet basic human needs, such as access to clean water, food, sanitation and shelter. They help meet social needs such as communication with others and enable in the process of self-actualization, for instance by providing us with tools such as music instruments with which we can express ourselves creatively. But not everyone has equal access to these technologies, or the knowledge to work with them in a safe, productive and meaningful way. And many of these technological advantages come at a price; directly or indirectly, they challenge our wellbeing and that of others. Look around you in a public place and notice how many people stare at their mobile screens instead of talking to each other. Certain behavior ‘performs’ better on social media which favors more extravert personality types and makes the introverts among us even more invisible.

Many technologies challenge our wellbeing and that of others

On a larger scale, digital algorithms keep people in their social media bubbles which threatens our capacity for empathy and solidarity. They reinforce toxic (dis)information and online hate campaigns. Our greed for smartphones and other electronic gadgets makes that our planet is being exploited for rare earth resources. This often happens in conflict ridden areas such as The Congo, where the extraction and trade of minerals such as coltan only sustains the conflict. And these are just some examples.

Survival of the best equipped

So, when do we experience technology privilege? Well, on the most basic level you could say that we experience technology privilege when technological innovation does not bother us. Because our belief system (Capitalism?) tells us these innovations will only bring us advantages; ‘it is new, so it must be good’. We are able to close our eyes to the disadvantages of technology because we trust in the fact that these probably won’t affect us or our environment negatively (for example, see this article on nextnature.net about the Facebook Outage of 2021). The ultimate expression of techno privilege on this level is probably that moment when you can afford the luxury of forgoing technology. For example, by planning a ‘digital detox’ to focus on other aspects of your life, such as exotic holidays and yoga retreats.

We experience technology privilege when technological innovation does not bother us

On a more profound level, we experience technology privilege on a planetary scale. Technology provides us with an unearned advantage over other earth inhabitants. 20.000 years ago Homo Sapiens, the species of modern humans we belong to, outperformed other human species such as Homo Neanderthalensis, simply because we used more advanced technologies. We created simple tools from natural resources such as flintstone to create spears and arrowheads which we used to hunt and kill animals. The woolly mammoth did not just get extinct by some unhappy accident like a meteorite crash. No, we ate them all… because we could! Today, the employment of tools to meet our needs for nutrition manifests itself in the way we keep, breed, kill and eat animals on an industrial scale, A process that is carefully outsourced and largely invisible to most of us; check your technoprivilege! Picture modern day factory farming: fertilizer to grow and machines to harvest the crops we feed to animals, artificial insemination technology, milk robots, battery cages, transportation networks, slaughterhouses, global markets… In the industrialized world of today, the Darwinian axiom ‘survival of the fittest’ seems to come down to ‘survival of the best equipped’, at the expense of those without access to the most advanced technologies.

But what if, in a bizarre twist of karma, the most advanced technologies would turn against us and marginalize Homo Sapiens as a species altogether? For example, what if an artificial intelligence would reshape the world according to its own binary logic and mechanical desires, instead of the needs and values of humans made of flesh and blood? In the science fiction classic The Matrix (Wachowski’s, 1999), humans serve as living batteries to provide energy for an ubiquitous simulation created by a computational super intelligence.This is of course a fictional doom scenario that could be discarded as meaningless Hollywood escapism, which might be partially true. But the good thing about these kinds of doom scenarios is that they provide us with a vision of the things we don’t want to happen. In that sense, these stories can be seen as some kind of mental device against which we calibrate our human values, dreams and ambitions, while being in the present.

Let’s acknowledge our technology privilege!

So is there anything we can do? I believe there is. To start with, we can become more aware of the role that technologies play in our everyday lives. To be more precise: we can become more aware of the power dynamics at work. We can ask ourselves at any given moment: does this technology X empowers us and our fellow humans? Or does it make us unnecessarily vulnerable (i.e. dependent, addicted, exploited etc.). Then, we can become more aware of the impact of technology on our environment. Again, we can ask ourselves: how is this technology produced? Who owns it? Who gets rich and who or what is being exploited? If I pay for this technology, to what world do I contribute? One where all technology is centralized in the hands of a few ultra rich white men, or one where technology is owned by the people?

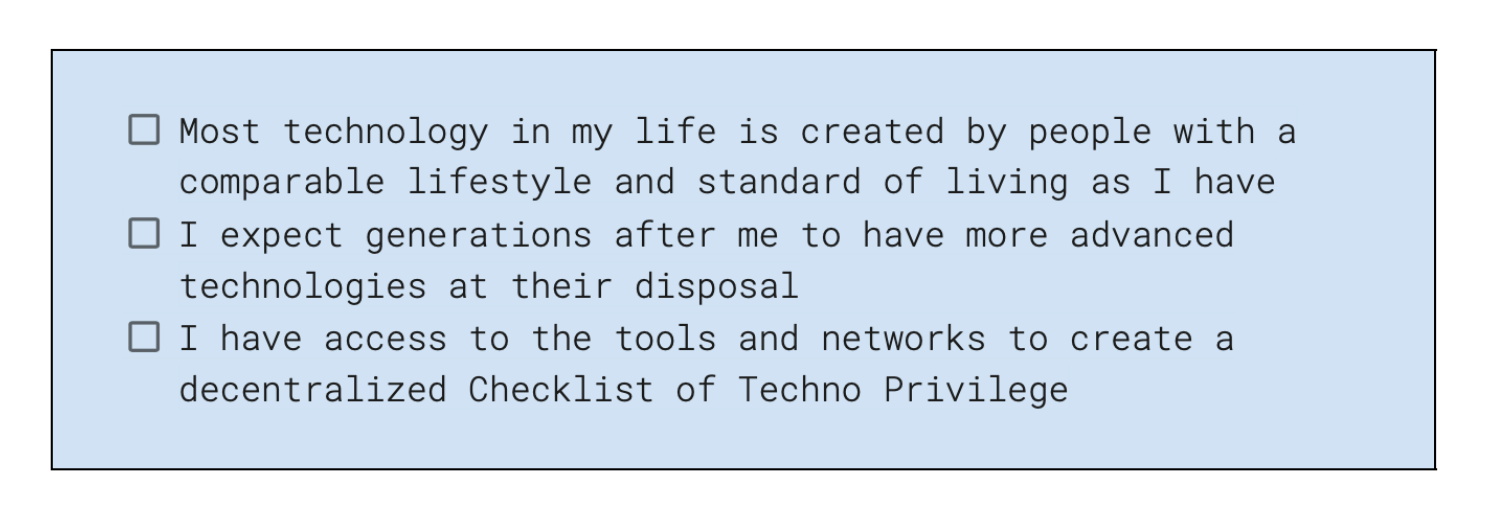

Awareness does not just happen overnight, and the process of becoming aware is never finished. So what I suggest here might be quite a big and abstract task. However, a simple and concrete way to start is by acknowledging our own technology privilege. Again, I take inspiration from Peggy McIntosh. Part of her essay is a checklist of statements which codify the effects of white privilege in her own daily life. For example: ‘I can choose blemish cover or bandages in “flesh” color and have them more less match my skin’, ‘I can turn on the television or open to the front page of the paper and see people of my race widely represented’, or ‘When I am told about our national heritage or about “civilization,” I am shown that people of my color made it what it is’. Inspired by this list, I start creating my personal checklist of technology privilege. It consists of a list of technology privileges that I can ‘count on cashing in each day’, to speak with McIntosh in mind.

I start creating my personal checklist of technoprivilege and I want you to help me make it better

My intention is to publish the checklist on various platforms so that others can work with it, too. I know that I can not do this alone; one aspect of acknowledging your privilege is to acknowledge the limitations of your personal experiences and thoughts. Therefore I call upon your help, dear reader. I want you to look around. Inside your house, when you go to work or to school. Keep an eye out for any experience where you feel that you, or somebody around, you has (or lacks) technology privilege. Sometimes it will be obvious, sometimes it will be subtle. Observe carefully and keep a list of your observations, be like Peggy. You may keep your observations to yourself or share them with others. However, I would be most grateful if you would share them with me. I believe that only together, we can make sure the checklist represents multiple voices, preferably from all corners of the world and from all kinds of demographics. It’s very well possible that there is not one final checklist, but several versions of the checklist floating around on the internet and where not. We have to start somewhere, so I suggest we start here and now. For me, it started today already #checkyourtechnoprivilege

Call for entries: send in your checklist!

If you can relate to the above and want to contribute to my quest, I challenge you to create your own Checklist of Technoprivilege and send your version to technoprivilege [at] nextnature [dot] net. Together with my team, I will review all contributions and edit the most valuable elements into a new checklist. Of course, you will be credited accordingly.

Share your thoughts and join the technology debate!

Be the first to comment