The act of eating earth is something long forgotten in western history, but not in its completion. There are still communities of earth eaters around the globe, practicing “geophagy” for a variety of reasons. We spoke with the Museum of Edible Earth, a travelling museum dedicated to the prosperous amount of soil samples.

Why this project?

SasaHara (they/them), artist and project manager of the Museum of Edible Earth: It all starts with the earth craving of Masharu (they/them), the founder of the MEE. They have always been drawn to eating earth, and about 9 years ago they started researching if other people had the same craving. Finding out that “geophagy” (the scientific name given to the action of eating earth and soil-like substances) is practiced culturally in many countries since ancient times. From there starts an exploration of geophagy with field-trips and collecting earth samples. After a while, a need emerged of organizing the collected samples. In 2017 the Museum of Edible Earth was born.

Is it a fetish? A lifestyle?

Rather than a fetish or a lifestyle, I would say it is more of a cultural practice that is sometimes rooted in medical or spiritual purposes. masharu or I are earth-eaters who don’t have a cultural relationship to geophagy (we weren’t born in a cultural environment where it exists). So for us it could somehow connect to the fetish. I know masharu has sometimes referred to earth eating as a fetish of theirs. On my side I like to call my edible earth a “totem” of mine, a practice I intentionally incorporated in my daily life that helps me ground myself and take care of my body-temple.

I like to call my edible earth a “totem” of mine, a practice I intentionally incorporated in my daily life that helps me ground myself and take care of my body-temple

Collaborative performance of masharu, Kristi Oleshko, Anton Tarasenko and Ekaterina Sleptsova during Potok Festival, Russia. Photo by Evgenija Beljakova

Who is this for?

Geophagy is for anyone who likes eating earth, who finds pleasure in the creaminess or crunchiness of clay or chalk (or any other mineral treasure).

What are the health gains of eating earth?

Earth is mostly composed of minerals. Clays can provide us with calcium, magnesium, silicate, iron and so on. There is an ongoing debate on the nutritional value of clay. Some scientists argue that the “bio accessibility” of clay is very low (a human body cannot extract a high quantity of the clay components during digestion). Others argue by explaining that the above mentioned minerals are needed by the human body only in small amounts, and that the low bio accessibility still allows us to benefit from their nutritional value.

Beyond this debate, an undiscussed property of the clay and other mineral goodies (such as charcoal) is their absorbing and neutralizing action that finds roots in their molecular structure. In other words, eating earth helps cleansing the digestive system, and protects digestive organs against acidity. I personally eat clay every day in order to control my acidity and avoid digestive pain.

I personally eat clay every day in order to control my acidity and avoid digestive pain

Exhibition at Center for Creative Industries Fabrika in Moscow, Russia. Photo by Tanya Sushenkova

Tell us about the science behind the project.

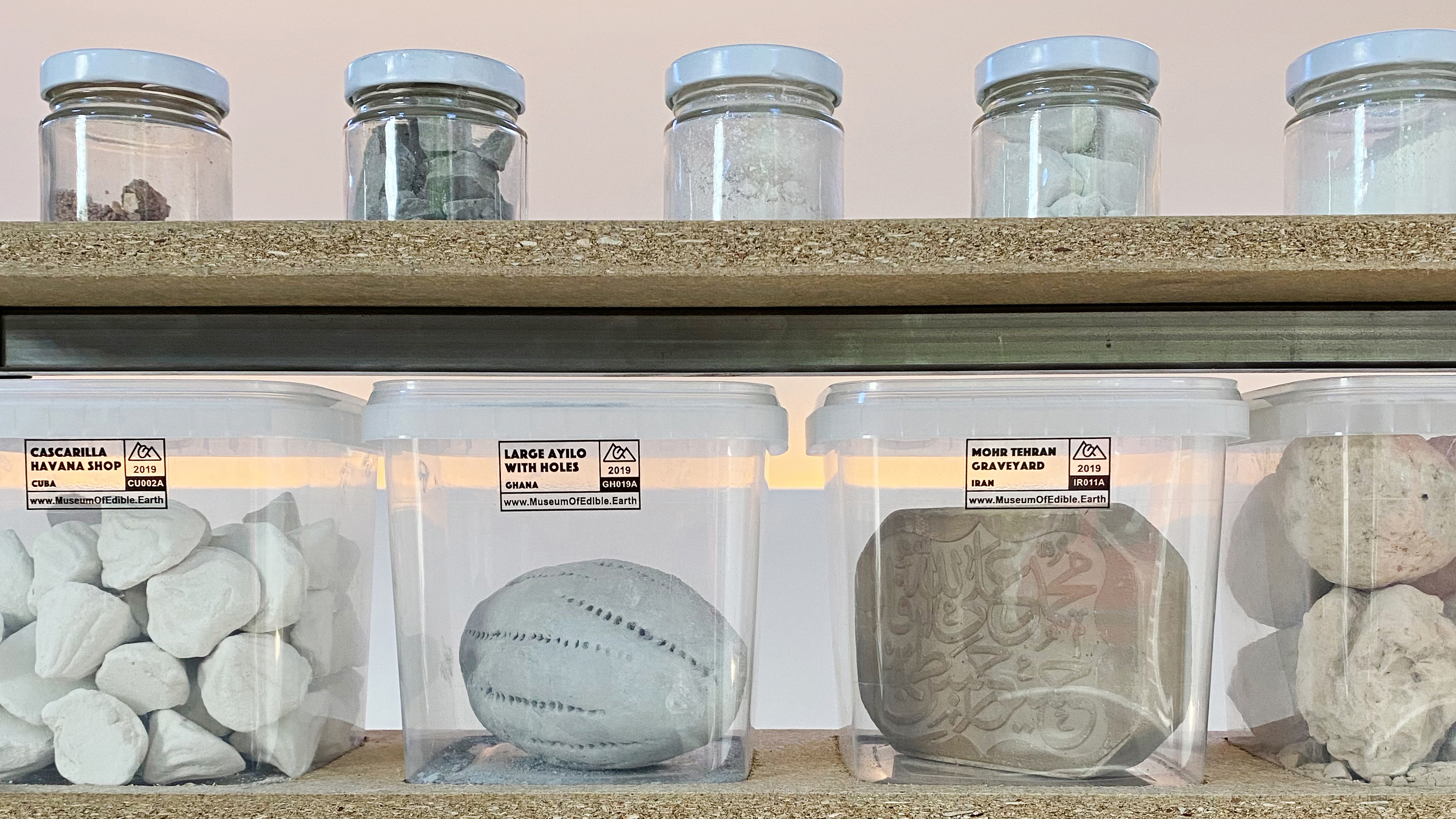

The MEE intersects with various scientific processes. A first one is ethnological research: trips to areas where geophagy is culturally practiced, meeting the communities, witnessing production processes and spiritual practices. The project is then based on an archival work: we weigh, label, identify and describe each sample of the collection which are then stored sustainably. We also digitally archive all of our collection in a very detailed way with precise localization, weight, price, local descriptions and any information that will keep the memory of its origin fully accurate. A public interactive database has been created in 2020 by the web designer Raphäl Pia (studio dindon), museumofedible.earth! There our audience can access the collection through photos, videos and textual description, as well as leaving feedback of any format to participate in the data gathering of the MEE.

The museum has collected over 400 different types of soils from 34 different countries in its database. How can we gain access to this?

The collection can be approached at our Amsterdam studio through reaching out to us. The MEE is a travelling museum so the collection is also dividing itself in smaller parts exhibited internationally (this year in Russia, the Netherlands, Hungary, Zimbabwe and Armenia, with also an award won at Ars Electronica and a 2 years display at their Ars Electronica Center in Linz). As mentioned previously it also can be approached digitally at museumofedible.earth!

And how to use it?

The best way to connect to our MEE is by tasting its samples! We like to organize earth tastings, during these events we also share stories with the participants.

Can people add?

Yes! An important process of the MEE is the earth exchange. Many of our samples have been acquired through exchanging some of our earth with people against some of theirs. We are welcoming in the collection all earth that is eaten by at least one person.

We weigh, label, identify and describe each sample of the collection which are then stored sustainably

Product design by Basse Stittgen (NL/DE). Build-up assistance by Asia Semeniuk (PL/NL). Curated by Ola Lanko (NL/UA) in diptych (NL). Photo by Alexandra Hunts

As humans we have alienated ourselves from nature, can eating earth teach us to become more ‘natural’?

Clay, and other types of earth, have an important spiritual component. Many creationist myths tell the story of humanity created from clay. The ceramists will always talk about the spiritual energy of the clay shaping. Many of the cultural geophagic practices connect to spirituality. In Guatemala, the Pan de Dios (clay tablets with religious inscriptions) are sold in some places as edible products for spiritual cleansing. The Turbah (or Mohr) in Iran is also an engraved clay tablet that some believers also like to eat.

The eating of earth participates in our connection with the fabric of our planet, the invisible web that connects all. It grounds, and provides a great material for reflection: What if the earth is contaminated? How will the upcoming life cycles remain sustainable if the earth isn’t cared for?

Or, put differently, what does geophagy reveal about our relationship with nature?

Geophagy brings us back in touch with the deep cycles of our planet. Organic matter living, dying, going back to the earth and eventually getting recycled into new mineral forms that allows new life to thrive. It emphasizes deeply the need of a healthy soil, a “tasty soil”, it points finger at the contamination of soils by the chemical industries and makes us think of its almost irreversible nature. It helps us to think of how to start again and start better.

Geophagy brings us back in touch with the deep cycles of our planet. Organic matter living, dying, going back to the earth and eventually getting recycled into new mineral forms that allows new life to thrive

Collaboration with the Pasirputih Foundation (ID), Lombok. Photo by Masharu

Tell us about the western cultural perspective on earth-eating.

While in Europe and the USA eating earth was as well a cultural tradition, at the moment it is officially regarded as a psychological disorder, known as pica, which is included in DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). However, some people in the Netherlands still practice various types of earth eating. A number of popular brands available in health shops, such as Ecoplaza and Biomarkt, provide clay officially meant for internal use.

Besides a number of clays from Tanzania, Nigeria, Ghana, Congo and Suriname are available on the Dutch market in cultural shops as unlabeled products.

Does the project aim to change this perspective?

No. We do not seek to persuade, and actively change the western perspective on geophagy. Our work is only about sharing the existence of Geophagy, keeping its heritage alive, creating spaces for earth eaters to meet and enjoy geophagy without taboo, and allowing others to discover it. A big part of our project resides in interactive moments where important discussions take place, but we do not aim at changing minds, only proposing food for thoughts and earth to eat.

How? Can you say something about the history and traditions of geophagy in different countries and/or communities?

I mentioned the Turbah and Pan de Dios, both relating to religion. In Suriname, an important geophagic practice is based on the Pimba (or Pemba), a kaolin (white/pink clay) shaped in the form of a ball. It is a common snack to eat, sold on many markets. But the Pimba is also used spiritually, in the Winti religion, some rituals involve the Pimba to cover the skin and to eat.

Many other stories can be told, I propose any curious eye to visit our museumofedible.earth website for more.

Our work is about sharing the existence of Geophagy, keeping its heritage alive, creating spaces for earth eaters to meet and enjoy geophagy without taboo, and allowing others to discover it

Exhibition at Center for Creative Industries Fabrika in Moscow, Russia. Photo by Tanya Sushenkova

Are there more species—other than humans—that practice geophagy?

Indeed many animals eat earth, such as many birds who need it for digestion. Some monkeys and elephants also look for caves to lick rocks for their mineral needs. We have been told by Indonesian colleagues that parrots also eat clay to cleanse their digestive system from toxic elements.

Does climate change influence the quality of the edible soil?

Not that we know!

What’s next for the Museum of Edible Earth?

The travelling aspect of our collection is a rather new component which we want to perfect. A storing design has been created by the Amsterdam-based designer Basse Stittgen, MEE features will be developed in the coming periods to enhance the collection’s access and overall space. A new axis of research for the upcoming year will be the notion of Taste. We have started to gather data of our audience’s tasting experiences, which we want to use to develop new formats.

Exhibition at Center for Creative Industries Fabrika in Moscow, Russia. Photo by Tanya Sushenkova. Photo by Masharu. Cover photo by Jester van Schuylenburch