Millions of years ago, humans evolved on the savannah. There were no smartphones, cities or highways. Our living environment has changed completely. The way we currently build is not sustainable. We will have to develop a sustainable living environment that matches our human needs, intuitions and potential.

The natural habitat of the polar bear is the Arctic. The natural habitat of the scorpion is the desert. How about humans? What is our natural habitat? More than half of the world’s population now lives in urban areas—increasingly in highly-dense cities. It has been estimated that by 2050 almost 70% of the world’s population will live in cities. The mass shift to urban living means more buildings, but the way we built our cities is not sustainable. Why? All buildings today have something in common: They are made using Victorian technologies. This involves blueprints, industrial manufacturing and construction using teams of workers. All this effort results in an inert object, which means there’s a one-way transfer of energy from our environment into our homes. Not very sustainable.

While the building practices of the 20th century may have suited the industrial era, the 21st century presents a set of challenges that asks to reconsider these parameters anew: Mass urbanization, the rise of artificial intelligence, the decrease in biodiversity and growing inequalities. Certainly, the architecture of our built environment comes with many challenges. But it also represents a playing field for new opportunities. Rachel Armstrong believes that the only possible way for us to construct genuinely sustainable homes is by placing them in a constant conversation with their surroundings. In order to do this, we need to find the right language.

Dr. Rachel Armstrong is Professor of Experimental Architecture at the Department of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, Newcastle University. She is also a 2010 Senior TED Fellow and pioneer of Black Sky Thinking, which is establishing an alternative approach to sustainability. It entails a close reading of computational properties of the natural world to develop a 21st century production platform for the built environment, which she calls ‘living’ architecture.

She radically re-envisions our approach to co-inhabiting space, and offers a new framework for building practices able to deal with the wicked nature of centuries' fundamental challenges through Experimental Architecture. It shifts away from the principles of the industrial age towards conditions and a set of tools for an ecologically engaged human development. This enables a new collaborative interplay of various disciplines, agents, material flows, processes and entanglements that together form a ‘choreography of space’—one that allows the exploration of a more sustainable way of co-inhabitation.

Since her early work on protocells (a group of chemicals without DNA that visualize and perform the properties of living organisms to potentially constitute the material for metabolic living environments) she explored the use of new living materials in the construction sector to move towards metabolic relationships and explore the means of self-repairing and living architecture for an ecological era. As a designer, chemist, science-fiction writer and educator, she blurs the boundaries of the imaginative and real spheres to design in the unknown, combining theory and practice.

Armstrong encourages us to think even further than ‘just’ outside-the-box and stimulates a dialogue and new narratives among human and non-human agents on co-inhabitation—to leave behind our dying buildings. As such, experimental architecture does not lay down a fixed road map for the future of our built environment, but builds upon continuous experiments and prototypes that are previously assessed and collectively endorsed. Ultimately it provides the basis for creating new meaning and solutions to suit the needs of the 21st century.

Your research on living architecture displays how artificial biological systems can function as a living organism. It has won numerous awards and has been recognized as a pioneering and revolutionary approach towards transforming the built environment. Can you tell us a bit about the beginnings and the current state of your work you do?

When I first started with the concept of directly applying and defining the processes of living things, it was still a field when the notion of bio design did not exist. I was looking at the fabric that life provides. My work on protocells (a series of chemical reactions that sustain living organisms) asked the question: How do you design and engineer this process of metabolism? Metabolism connects the cycles of life and death. It enables a regenerative condition of creating structure and process simultaneously. I was looking at the foundational principles by really thinking through its theory and practice - rather than applying existing ones. Developing a theory constitutes a large part of my work, the other part is enabling a complementary practice.

Recently, we have been working with the masters of metabolism: Microbes! The foundational Living Architecture project ran from 2016 to 2019. It was based on the idea that we need to change the infrastructure of our buildings before we can change the way that they work. Despite significant contributions to embodied materials and the negative impacts on the environment, our dependence on fossil fuels is far more toxic right now.

The Living Architecture has developed into numerous extraordinary projects as demonstrated in the application of microbes to build a synthetic reef below Venice to strengthen its foundation and keep it from sinking. How did the Living Architecture initially come to be? What type of changes and questions does it propose to contemporary architecture/ the way we currently inhabit our buildings?

In 2011, there was this great project by Philips, the ‘Microbial Home’, a proposal for an integrated cyclical ecosystem, which was basically a kitchen that was feeding off its own waste. There were some wonderful design objects that came out of that. It was a concept which could be taken into reality. The Living Architecture project was born in that same period. It was informed by the speculative design of the Philips project, combined with the latest developments in synthetic biology, artificial intelligence, engineering, and anthroponics (a recirculating soilless agriculture system that uses natural bacterial cycles to convert human bio waste into plant fertilizer). There was this big condensation of how do we actually take waste from a home and use that raw material for our living?

With the technologies of synthetic biology, the living architecture turned household waste, specifically liquid waste, into bio electricity and other forms of biomass. It further recycled water immediately within the home or purified it to return to the environment. Our presence in the space marked by our actual activities of daily living are fed back into regenerative systems - essentially what our soils do.

We were creating the circular economy of a household. The ‘economy’ element is very important. We can place design objects within capitalist systems that reinforce these notions of individual privatization, forms of exploitation and inequalities. Yet, it leaves use with the questions: How do we ethically design?

How do we ethically design?

How do we start to break the most fundamental traits that are keeping us in this toxic state that we are living in? How can we realize the microbial commons within the household? Can we think of a new economy of the household that not about consumes from a market, but positions us as a catalyst of evolution and cooperater of nature?

In the 21st century, we can actually see some of the processes and pick the ones that we want to live alongside. That brings to question a lot of different ethical considerations. First of all the nature of the person. Since 2001, we have heard about this idea of the human microbiome (the collection of all the microorganisms living in association with the human body). Only 10% of our bodies are actually human cells, the rest are microbes. Who is this ‘I’ that we are designing for? Who is this family that we are designing for? And how do we develop inclusivity and sustainability within that? So the integral question of this work is: How do we live? What are the mediums through which we start to connect to the more-than-human realm?

Only 10% of our bodies are actually human cells, the rest are microbes.

From green roofs to entire high- rise residential buildings covered in trees (e.g. Bosco Verticale in Milan, Italy), integrating biological elements and imitating natural cycles has already become quite prominent in the building sector. In line with this development architects (Stefano Boeri) start to value the natural elements for more than just their ecosystem services/ utility but as inhabitants of the building and the city giving them a different position and rights in the planning process. As the variety of non-human species are earning more recognition in decision-making how do you envision to connect with non-human species through experimental architecture? What are the mediums through which we can communicate?

One of these mediums is artificial intelligence. Its role is to observe the microbes as the microbes are pooping out electrons. If it is not going well, Artificial Intelligence opens up the flow channels that feed the microbes more stuff. It is observing the microbes because we cannot see them directly. Artificial intelligence is also part of this giant pet because you start to engage in a condition of care not just exploitation. Within bio design you would normally think of making materials by working with nature based systems. First, you get into a state of liveability and then you kill them. We need to find out how we can actually extend that relationship to think of their life beyond the utility of the human. We have to figure out where the gives and takes are in these relationships. I quite like Mycelium. Sometimes I just hang around fields of agricultural waste and some mushrooms pop out. That looks amazing! It is not all about surrendering human integrity to the more-than human-world. It is actually going through the work of what are the ethical conditions in which we can coexist with others which may change from moment to moment.

We need to find out how we can actually extend that relationship to think of their life beyond the utility of the human.

Essentially, a lot of this really is about just thinking about what liveability is. How the human engages with more than others. This then includes technologies like artificial intelligence . Once you have artificial intelligence in the system, you can start to think about blockchain contracts and social contracts. What kind of contracts can be built into the performance of your house? Do you have access to water and electricity? Do you make certain biomolecules in your household that are useful to somebody down the road? You can start to build an idea of an ecological lifestyle that is not just about the energy consumption or resource consumption within an industrial framework, but can actually reference other economic systems and other social structures. To make sense of the living architectures, we really need to do that hard work on the economics and politics mirroring power relationships between bodies, resources and access. These are all really fundamentally important because we can see the external world today, and we can appreciate the challenges that established power structures present particularly within design.

So, you established the notion of living architecture. Now the continuation of the research is looking into the conditions of living architecture through Experimental Architecture. What is it? How exactly did experimental architecture come to be? How did your take on the concept evolve from its original roots?

Experimental architecture is the tradition in which the conditions of livability are challenged. It started out as a practice to disrupt existing power structures. Peter Cook and Archigram - a famous group of architects experimenting with radical approaches towards architecture - were thinking of using technology to re-empower the public against the top-down processes of urbanization including land ownership and housing development. In the 1960s’ technotopia, they were raising people's individual needs. Experimental architecture was shaped by very techno-optimistic elements. With Lebbious Woods, experimental architecture became much more critical. He used drawing as an experiment, a way of interrogating ideas since you do not have to actually build it. They are the course concepts. The continuation of experimental architecture, the one that I do, focuses on the process of bringing from the paper into the laboratory. Everything I do and I am going to do, is a prototype—a manifestation of the ideas of possibility—that invites further questions.

Everything I do and I am going to do, is a prototype—a manifestation of the ideas of possibility—that invites further questions.

The practice becoming more popular is actually what it is about. For example, Innsbruck and Bartlett School of Architecture have an experimental architecture department. As architecture and design gain validity, both in academia and in industry, we also observe more people with practical projects approaching experimental architecture. In response to a pitch on a building, experimental architecture asks: What is the status of its design in terms of the cutting edge sustainability? What can we actually make? Where are the questions? Where can we actually position our commercial project within a landscape of technological—but also ecological advances? I would say in some ways, the vast experimental architecture started out as the paper architecture through the laboratory, and building ambitious experimental relationships from engineering and science, as well as the arts and design.

As our world becomes increasingly complex and our challenges more ‘wicked’, collaborative efforts of actors with diverse backgrounds to design far-reaching and inclusive solutions, have gained in importance. Can you say something about the multidisciplinarity of experimental architecture?

The practice is fundamentally multi-disciplinary integrating cutting-edge science, technology, arts and design. Essentially, it is creating an innovation process with the 21st century. It is not just up to scientists to create something while artists and designers find out how to make it socially relevant. I must say the arts and design are absolutely fundamental if you want something ethical, socially appropriate and nuanced. Artists and designers have to be involved from the onsets. All disciplines are engaged right from the onset of the concept. It is a collective practice. There is a time when the collectives gather around a particular project and a set of funds. Yet, we need to figure how to nurture the continuation of the ideas from the collaboration. We need to figure out how to keep on asking the questions without any funding. A really important part of experimental architecture is to be able to think with nothing. We are not always in an environment where you can get a few million dollars to explore cutting edge technology. Particularly when you are working with scientists because running a lab is expensive.

It is not just up to scientists to create something while artists and designers find out how to make it socially relevant.

Your work is informed by theory and practice but with the notion of science-fiction, the artistic component is added to the equation. You have also written science fiction books. Can you say something about the role of fiction in experimental architecture?

I have written three fiction books: Origamy, Invisible Ecologies and Decomposition comedy. Each of these books take an idea for a stroll and start to reimagine the world. To me, that is the role of fiction. The 21st century experimental architecture needs to be not a practice, neither an extension of the 20th century architecture but a practice of worlding. How do we make our worlds? It is not enough to make a building and place it within the existing infrastructures and utilities. We have to imagine the other worlds like the work of film director and speculative architect Liam Young that moves between critica design and fiction to imagine a radical futuristic city. We have to actually conjure forth these worlds, inhabit them, be a character within them. Figuring out how this works is really essential for design. In contrast, if you cannot fall into that world, you are left with gaps in your design approach. This is where fiction has been in place. It is a way of getting a critical audience; a way of bringing people together around an idea to not come up with a simple answer but engage with a complex set of ideas. The good thing of fiction writing is that there is always something at stake. What are the disadvantages? What are the advantages? What happens to those characters that fall in between? It is not about a happy-ever after.

The 21st century experimental architecture needs to be not a practice, neither an extension of the 20th century architecture but a practice of worlding.

What does that mean for the role of designer in working with non-human agents? Where does the design begin and where does it end? Where does the agent come in and where does it end?

As a designer you do not lose your integrity, instead, you expand your imaginary spheres and the ‘relatings’ (the categories and groups you form to make sense of the world) that you do in order to bring forth your design. You consider many more factors. You understand why you discriminate. You understand why you exclude certain things and include others. It expands your ethics from an industrial designer to an ecological designer who has at least considered the impact beyond the human life span or the human use of the object. It has considered the participants or co-constituted agents within the design processes and giving them a politics.

It has considered the participants or co-constituted agents within the design processes and giving them a politics.

If we are using these agents in everyday life how do we care for them? How do we make sure their conditions are allowed on board? How do we make this more of a dialogue? A co-inhabitation exercise? The outcome of the design is not to consume and transform but to actually establish new cycles of exchange. The designer is exposed to unconventional influences within their sphere of imagination. The imaginary sphere and the narratives that they tell become more epic and more engaging because of that.

The vision you propose is a way to complete the cycle of what is the technosphere. So far, we have established the technosphere on top of the biosphere. While the biosphere has its own metabolism, the built technosphere around it is not sustainable. We leave all these things behind but we do not consider the underlying structures. What are you proposing to bridge these spheres?

The key is to have a connection. That is where metabolism comes in. Metabolism can relate to completely different worlds as we show in the living architecture project. We could bring together the light base world of photo- synthesis and the underground world decomposition and put them in dialogue through a chorus membrane. We could take that conversation because it produced electrons and turn it into a digital experience. It is really trying to develop the language so we can see those relatings. One of the problems of the metabolism of the living world is that it is invisible around us. We can get into the realm of phenomenology and we can get into the realm of vitalism as well as the material threat. They have interesting things to tell us, but we are no experts. Therefore, we have to conjure forth these other bodies that can help us negotiate these phases and these relationships better.

We could bring together the light base world of photo- synthesis and the underground world decomposition and put them in dialogue through a chorus membrane.

Is this where biomimicry comes in as a form of learning from nature and establishing this technological process?

I think the whole bio design movement has created a convergence between those established fields from bionics, to biomimicry to sustainability. It is drawing momentum into a spectrum of practices. There is something to learn from all of them. The critical message from those that have been practicing biomimicry, organicism and cybernetics, is about how we go forward with ethics.

The critical message from those that have been practicing biomimicry, organicism and cybernetics, is about how we go forward with ethics.

It is absolutely right to think about aesthetics, and structures and resource consumption and energy production but we have to do more than that. We need a shared framework through which we not only advance as individual designers but actually unite as a force of change. We do not all have to agree but we can be like biology itself. This means managing critical questions in a biodiverse way within the spaces that we are practicing through cross-informing and cross-pollinating. In a way, it goes against the industrial course of a designer to a practice of virtuosity that it is unique. It requires a more humble, more integrated but reciprocal form of design, for example, through practices of open source and crowdsourcing. It does not undermine the design process but gives designers a different toolset and a different set of challenges. The best designers really respond to that. The strongest outcome from this process are the narratives that enable the continuation of the projects into new forms. It is this momentum that brings about change in which biodesign is positioned in. We could get fractured into different pockets of practice, focusing on either biological shapes or on processes, but it is much more significant than that.

What would you advise young architects and designers?

For me it is about experimenting. It is about fundamental curiosity. Learn the craft that you have entered and then just identify what it is that you care about. Use the things that you care about, to rebel against what you have been taught. Find others that can help you in building your critical community. This is as important as developing yourself as a designer. You want to be among like-minded people that give you the moral support to do things that have never been done before; people that you can trust to be supportive. This does not mean that everything is unproblematic but you know who these people are when you meet them. You can negotiate with them- even microbes- on tricky issues to make proper decisions. Those communities are really important in design. We can get very fractured because of the competitive environments in which we are based, particularly in academia and industry. We do not have the design commons. Where are the design commons of ideas from which we as a profession can start to evolve and transcend those things that we are being measured and constrained by and do something else that entirely? Something that is sustainable. Something that does bring in income. Something that creates fantastic pieces. Something to be proud of.

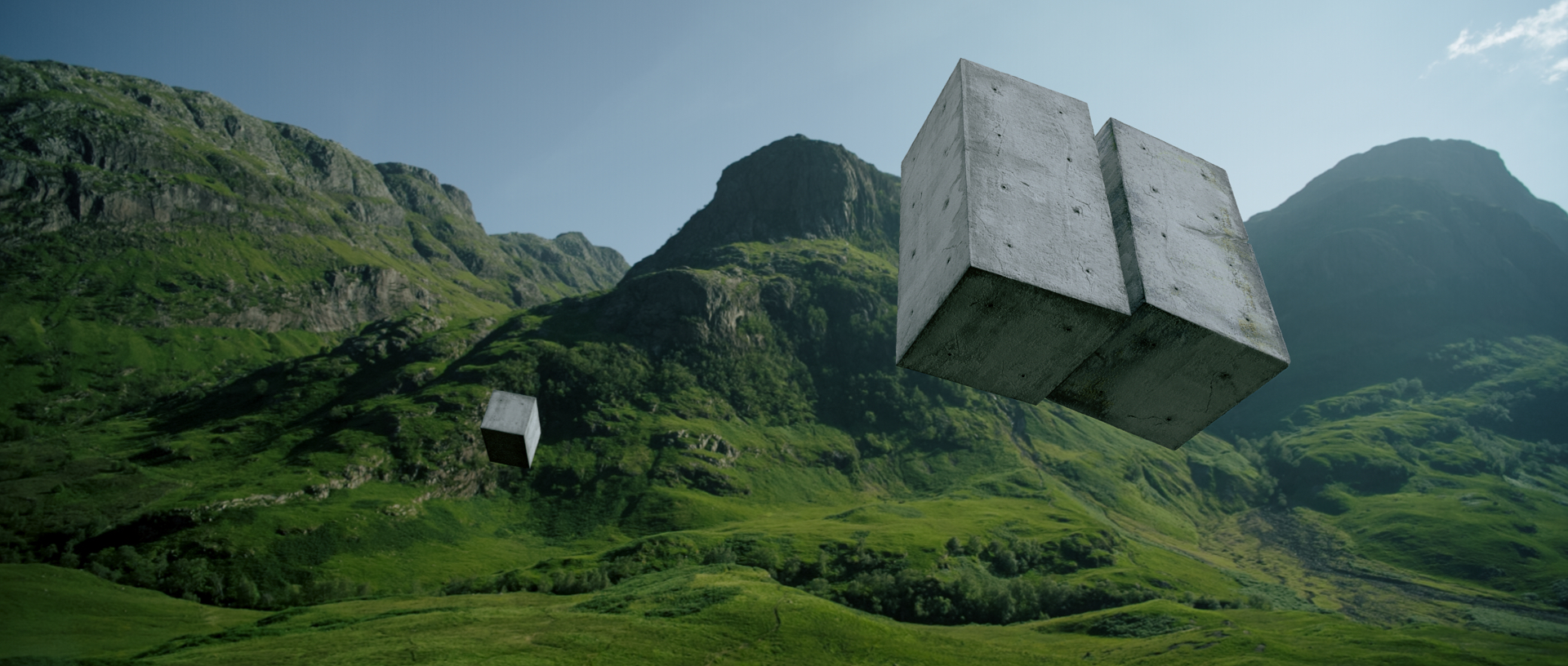

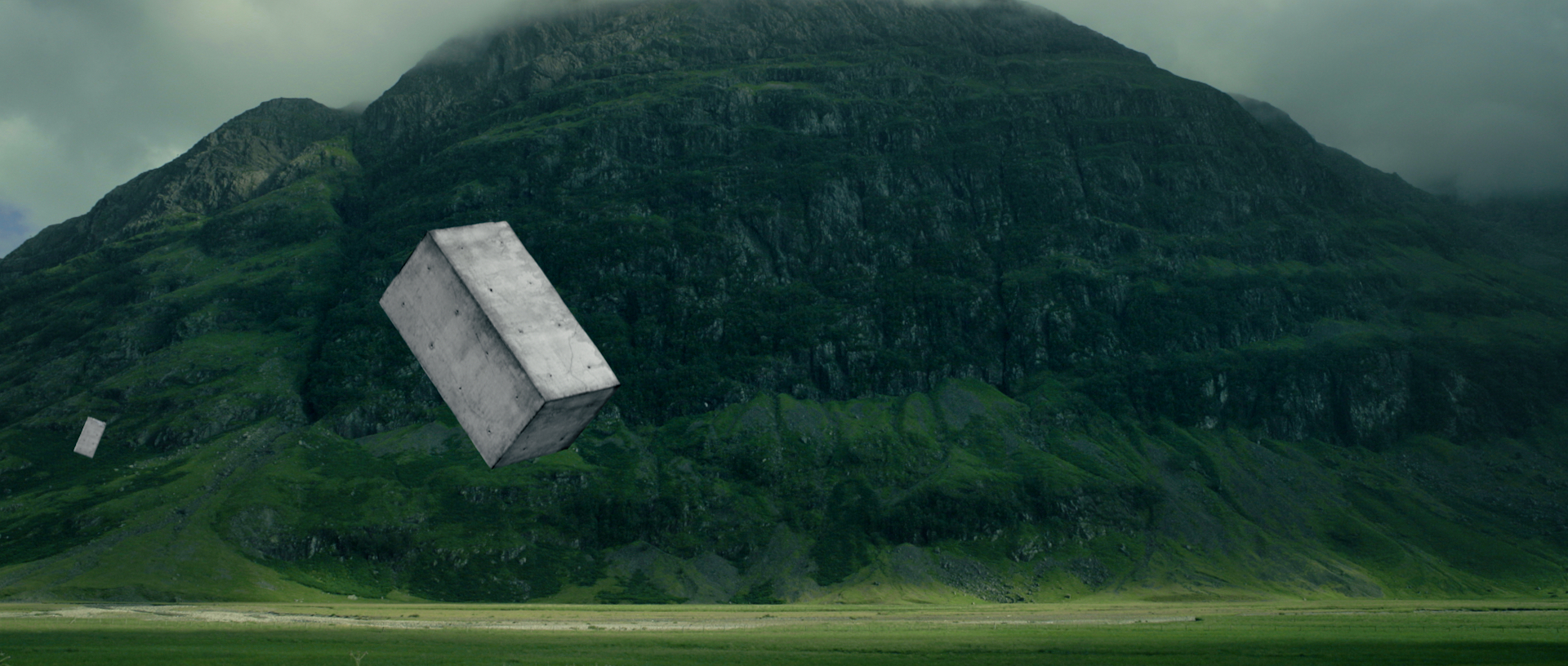

About the images: DRIFTERS (2018) is a film by Studio DRIFT and Sil van der Woerd, consisting of one floating concrete block, a concrete monolith that evokes a reaction to dream the improbable. Concrete builds the foundation of our homes, the very fabric of our built environment. It is the epitome of our urban jungles, the juxtapose of the green wilderness, and yet it has only been around for 500 years. Who knows, your next idea might be the foundation for a new world.