Visual Essay

What may life be like, centuries into the future?

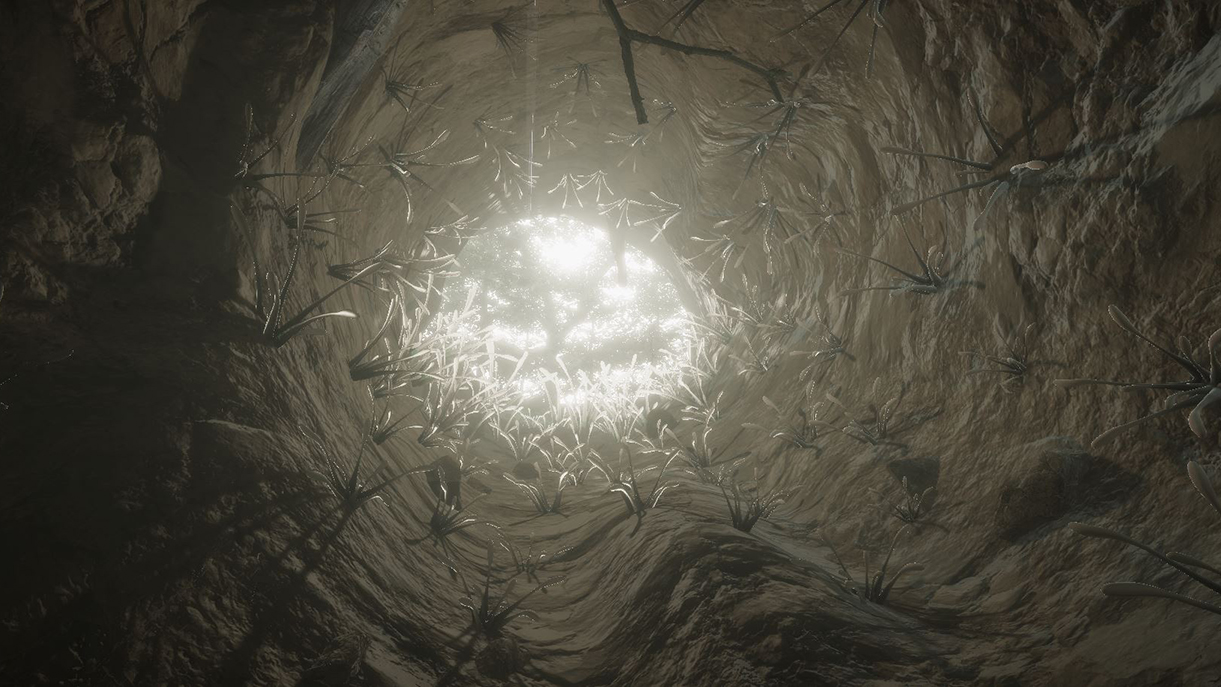

The world may have changed beyond recognition. But a damaged planet Earth may make the landscape of a fertile post-human biotope, rich and teaming with new artificial or enhanced biochemical life. Think genetically altered life forms, (chemical) robots, hybrid technologies, and autonomous intelligent systems. They are all sharing resources, habitats, bodies and information in an inclusive way on the premise of: symbiosis.

The idea of living in symbiosis is drawn from fables written by biologist, philosopher of science and feminist Donna Haraway. Her work toys between the known and the intuitive in a way that appeals to the imagination, somewhere between storytelling and science fiction. Stories that have the possibility of becoming future worlds. We met with Haraway to discuss two projects she inspired by documentary artists; filmmaker Diana Toucedo and immersive arts collective Polymorf. In Toucedo’s film, Camille et Ulysse, she us into the chthulucene: a post-human world somewhere in the future, where humans and non-humans live in symbiosis. Polymorf create the multi sensory world of Symbiosis, a spectacular VR installation that invites you to step into the chthulucene yourself, and to morf your own body into a post-human living creature.

Both works explore not the end of the world, but rather an ongoing one with multispecies, stories and practises as envisioned by Haraway. These stories help us speculate on how our landscape may evolve in the future, once technology has merged, evolved and even traded places with nature. A type of storytelling described by Haraway as speculative fabulation. Here is what she had to say.

We live in a time of such multiple urgencies. The speculative fabulation is a way of gathering the imaginative force.

Tell us about Speculative Fabulation and how this differs from science fiction, or even allow us to move beyond it?

Yes, I am deeply informed by speculative fabulation, indiginous futurism, afro futurism, science fiction, feminist fabulation. The fable is a very particular kind of narrative form of storytelling, that always contains a question. If the fable is interrogative, it’s usually edgy, not innocent, it proposes a world of possibility and of tricksterism. The fable is a very old form in many cultures. The speculative fabulation is to have futures that we, (whoever that we can be) can have the possibility of going on together. We have to first imagine going on together. To have the heart. The capacity to present to ourselves the propositional capacity, the imaginative capacity. That stimulates a kind of lust, it’s a kind of roar toward going on together. It’s a counter to cynicism. To depression, to giving up. It’s a counter to the refusal of cultivating the capacities to respond.

We live in a time of such multiple urgencies. The speculative fabulation is a way of gathering the imaginative force. To tell the stories for what might yet be and already are, but even more than we imagined. Once we tell these stories, we come to appreciate how much is already happening, that we should embrace and nurture. As well as what can yet be. So with speculative fabulation, I don’t answer that question by opposing it, to a category of science fiction. I’m the sort of person who works by addition. Not subtraction or opposition. I think all of these forms, which are related to each other, but not identical. These SF or string figure forms have a kind of venn diagram, in relation to each other. I work by that kind of addition. Rather than subtraction, to refine the one true approach.

You are known for rejecting the anthropocene, a narrative that accepts failure of humans, but perhaps something that we can rewrite. Could the anthropocene also be regarded as a fabulation?

It’s absolutely a fabulation. But I haven’t actually rejected the anthropocene. I have rather demoted it, so that it’s not at the top of some sort of hierarchy. Or it’s not at the end of some sort of orthogenetic evolutionary process, where this figure called man somehow takes over, at the beginning of this thing called modernity, or the various origin points for this figure of man. I demote the story of the anthropocene, to one of several that need each other.

I promoted the capilotoscene over the anthropocene for example, informed by Andreas Malm, and others. In order to foreground the fact that the system of global capitalism and racial capitalism, structurally conditions what can be possible, including storytelling. It’s not man as a species. It’s really a system of worlding called global capitalism that is a real thing. As well as a fabulated thing.

I propose the chthulucene, the time of the phonic ones, the time of the earthly. Bruno Latour calls it ‘terriens’. The times of the earthly ones that are not just in some ancient past, but are also now. That cultivating with the earthly ones of whom we are ourselves terrains. That being in and of the earth, as a way of addressing the urgencies of the anthropocene and the capitalitoscene, which is really important to me.

It’s not man as a species. It’s really a system of worlding called global capitalism that is a real thing. As well as a fabulated thing.

I also propose the plantationoscene. With others who I am deeply informed by, such as Sylvia Wynter and Katherine McKittrick, among others. The plantationoscene is really the system of, the link of systems particularly. The sugar plantations and the systems of slavery; new world slavery and chattel slavery, an what invented the plantion with its systems of double entry bookkeeping. The particular systems of division of labour for streak production. Separation of reproduction, from place and from agency over one's own capacities of reproduction. Both human and plant. The systems of the plantationoscene, really is the source of the possibility of industrial capitalism. People forget that, to our shame.

So it’s not that I’m against the anthropocene. I am really committed to not just infinite numbers of stories (it’s not just storying for its own joyful little sake, that’s fine too) but I’m interested in powerful stories within which it’s possible to make a difference.

There are going to be maybe eleven billion human beings on the earth. How will these human beings truly take care of each other?

Within the chthulucene you also do a call about making kinship. What does kinship mean to you?

Well, kinship. Marilyn Strathren, a social anthropologist says: “look, if you have a cousin and the cousin has you. Kinship is non optional, obligatory, enduring, through the generation relatedness in which you have each other's back.” You are for and with and of each other’s substance. Biological kinship is not the only kind by a longshot. Social codes are kinship, take up the substance of the world, including the bodies of human beings. They compose reciprocal kinds of obligation. I think of making kin as that nurturing, cultivating, taking on these: you have me, I have you, we have each other. We’re accountable to each other, and you can’t just walk away from it because you get mad at somebody. These are enduring accountabilities.

I also am of the view that human beings, as part of the disasters of the post World War Two era, have numbers. We are numbering this planet in ways that cannot be sustained. So that by the end of the century if we are lucky there are going to be maybe eleven billion human beings on the earth. How will these human beings truly take care of each other? Particularly as the burden of all of this falls way more on the poor. Particularly as the rich and our habits of consumption drain the earth dry. And we blame the reproductive habits of others. Whereas the reproductive habits of the rich, in all of its senses including consumption, are draining the earth dry.

So how do we make kin? Including perhaps, every child has the right to three or four parents, real parents! Who may or may not be each other's lovers. That parenting. I want a pro-child world. Not a pronatalist world. But a world that really cares about the young. And that is not the current world. So making kin has all of those meanings.

Staying with the speculative fabulation, do you still continue to write Camille stories?

I have not written any more Camille stories. I’m not quite sure what. Writing right now is taking really short, flavour burst forms and I haven’t done any kind of sustained composing writing. So I’m not sure what shape it will take, but other people are writing Camille stories. And doing Youtubes, and videos. High school kids are writing notebooks of Camille stories. The Camille stories have a life but I’m not their author.

Let this be an open call to the audience to write fanfiction on Camille stories! This interview is an excerpt from IDFA Doclab Live: Beyond the Cyborg Manifesto. DocLab co-presented with Eye Xtended during the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) moderated by Ruben Bart.