Geodesign #8: We have identified eight key defining moments as an introduction to this emerging design movement—from science fiction to post-human habitats.

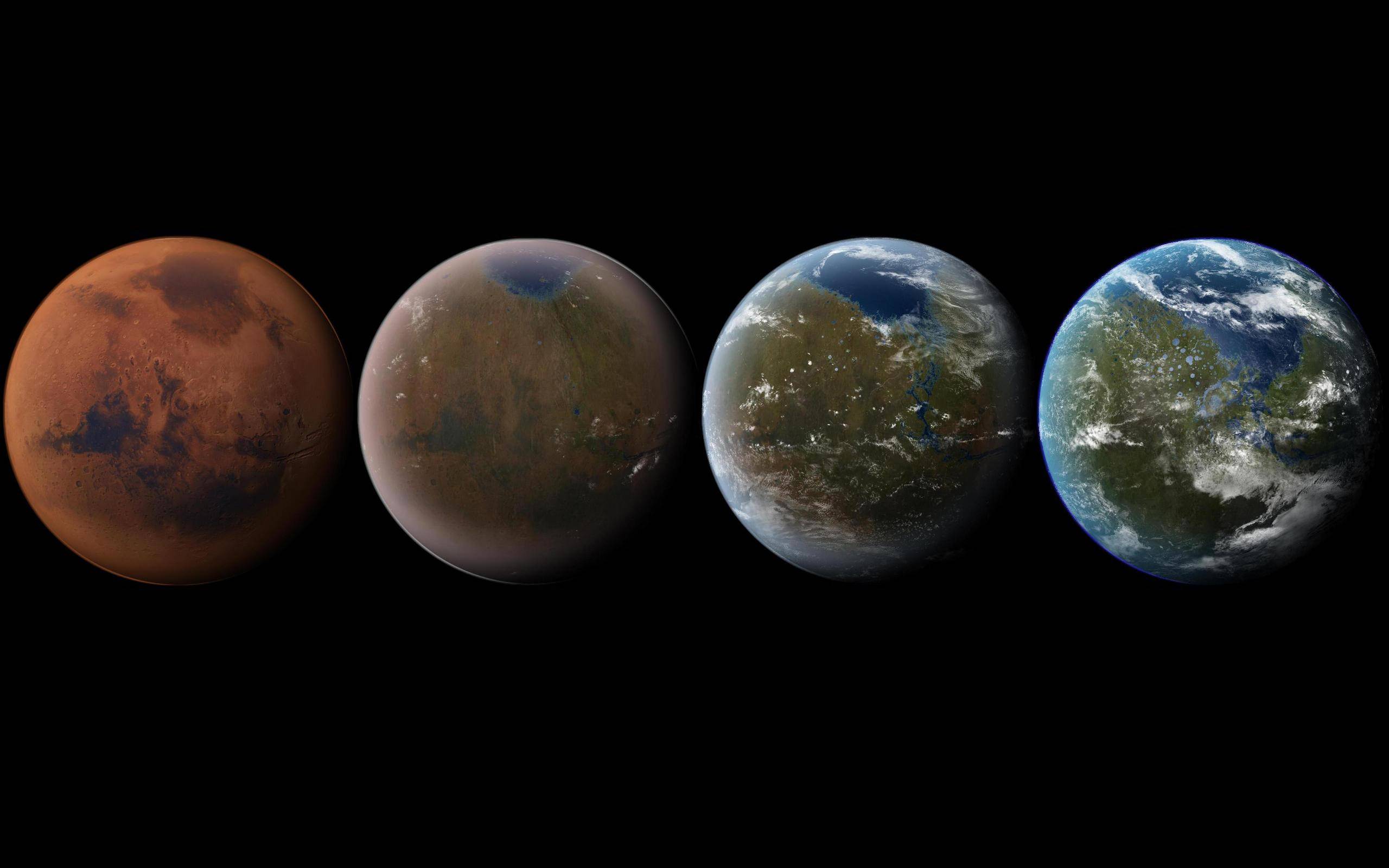

In the 2400s, mankind begins to terraform the planet Mars. Giant corporations, sponsored by the World Government on Earth, initiate huge projects to raise the temperature, the oxygen level and the ocean coverage, until the environment is habitable. Corporations work together in the terraforming process, but compete for the most outstanding contributions for advancing human infrastructure throughout the solar system and doing other commendable things; from introducing plant life or animals, hurling asteroids at the surface, building cities, to mining the moons of Jupiter and establishing greenhouse gas industries to heat up the atmosphere. Terraforming Mars Series.

What already exists as a science fiction series, book and even board game could one day become reality. Terraforming of Mars implies a planetary engineering project with the aim to transform the red planet to sustainably host humans and other lifeforms. By designing the planet’s surface, atmosphere and extant climate in an extensive socio-technological process, new novel ecological systems could potentially be installed. What seems like a distant future is nearer than we think. Elon Musk has announced to dedicate half of his fortune to preserve the human species and send a human to Mars as early as 2024. But how will we live as aliens on Mars? How will we terraform the landscapes?

We have already done it once before. For the past centuries, we have been terraforming planet earth. We have reclaimed land from the sea to build dykes and palm-shaped islands, created micro-climates favourable to our plant growth, redirected rivers and built an entire technosphere on top of the surface of planet earth.

For the past centuries, we have been terraforming planet earth. We have reclaimed land from the sea to build dykes and palm-shaped islands, created micro-climates favourable to our plant growth, redirected rivers and built an entire technosphere on top of the surface of planet earth.

Which brings to question if we want to make the same mistakes as the first time or if we strive to become better inhabitants to embrace an ethical multi-planetary existence. As we are leaving our human existence on planet earth behind to become Mars aliens, how will we design our post-human habitats?

Designing our post-human habitats

Every mountain path has been designed in a way for humans to reach the peak in the most comfortable and efficient way. Whether it is a wildlife safari, nature conservation area or urban park, despite being filled with a diversity of different biological species, they are still a spatial innovation built with a human in mind. Most of our perceived ‘natural’ areas are humanscapes. This is more obvious within our areas of inhabitations such as our cities. What if we break out of our anthropocentric concrete jungles and put non-human agents at the center stage of the design of our geoscapes?

What if we break out of our anthropocentric concrete jungles and put non-human agents at the center stage of the design of our geoscapes?

Post-human design does not imply a scenario in which we keep humans out of the equation; we merely emphasize the alternative perspective on design that shifts focus away from an anthropocentric position of observation and control. Humans are not the dominant species. Nonhuman entities such as bacteria, insects, algae colonies, and the technological systems take a prominent role in post-humanist design to decentralize the role of human judgment. It embraces the notion that creative agencies can be conferred. What if our habitats could co-evolve with us? And what if we could co-evolve with nature?

Thus far, we have been using Victorian methods to design our buildings and habitats in the 20th century. Methods which are not suitable to deal with the contemporary challenges from resource extraction to climate change. In order to be able to build truly sustainable homes, we need to be in constant conversation with our surroundings. So, how do you design and engineer in dialogue with non-human agents?

This is a question Next Nature Ambassador and Professor of Experimental Architecture, Rachel Armstrong, explored in her early work in the field of biodesign. She explored how living organisms can function as the building material with which we construct our homes. In a way, making our buildings a living organism that co-evolves with its inhabitants. In this regenerative process, designing our next habitat becomes an interactive process with various actors and agents.

In a way, making our buildings a living organism that co-evolves with its inhabitants. In this regenerative process, designing our next habitat becomes an interactive process with various actors and agents.

According to Armstrong this brings questions of the preconceived notion of ‘liveability’. What mental models do we employ to dream, live and design our habits? What relation do we foster with ourselves and our surroundings? How do our social structures mediate this relation?

As humans we will not refer to the second stage but rather draw different relations to our worlds. We need to ask further questions and continue to experiment co-inhabitation with other agents. This will bring about a new socio-ecological lifestyle with new technologies and social contracts to engage with nonhuman entities. In order to create a desirable habitat for all life forms including ourselves, we need to make sense of these worlds, through imaginary spheres, whether we are designing our post-human habitats on earth or any other planet.

Share your thoughts and join the technology debate!

Be the first to comment