This story is part of Next Generation, a series in which we give young makers a platform to showcase their work. Your work here? Get in touch and plot your coordinates as we navigate our future together.

What if living objects could re-connect humans with their menstrual cycle and change the way we perceive it? The patriarchal and capitalistic culture has perpetuated the stigma around periods by promoting the production of single-use products that have influenced the behavior of many generations. Recent studies have highlighted how some menstrual hygiene products and pain relief medication affect our bodies and the planet by interfering with the healthy microbes we live with. The vaginal microbiome plays a central role in preventing vaginal infections and resorting balance, as well as reducing symptoms of dysmenorrhea; severe menstrual cramps, which affect around 80% of those who menstruate. Recent graduate Lucrezia Alessandroni's project The Soothing Cup explores this with her Master's degree in Biodesign at Central Saint Martins (London).

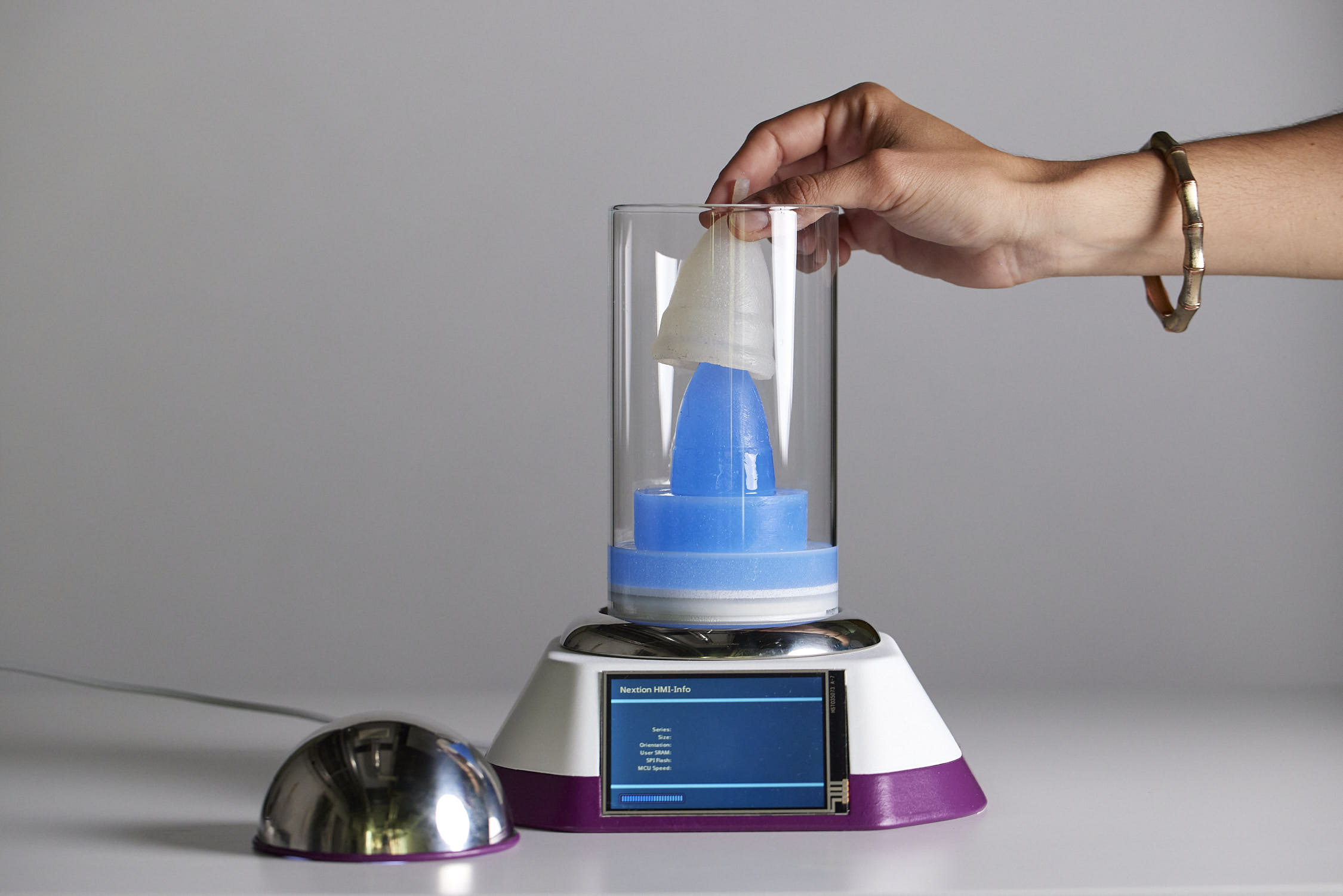

The Soothing Cup explores a speculative future where menstruators are deeply attached to their menstrual cups, establishing a mutualistic relationship as an alternative to chemically preventing periods. The development of an alginate-based hydrogel allows the cup to become a membrane able to interact with the vaginal environment. Thanks to an incubator that acts as a surrogate vagina, people who menstruate can cultivate their own anti-inflammatory bacteria and let them colonize their cups. When off-menses, the user can take care of the cup whilst increasing knowledge and challenging the stigma around periods.

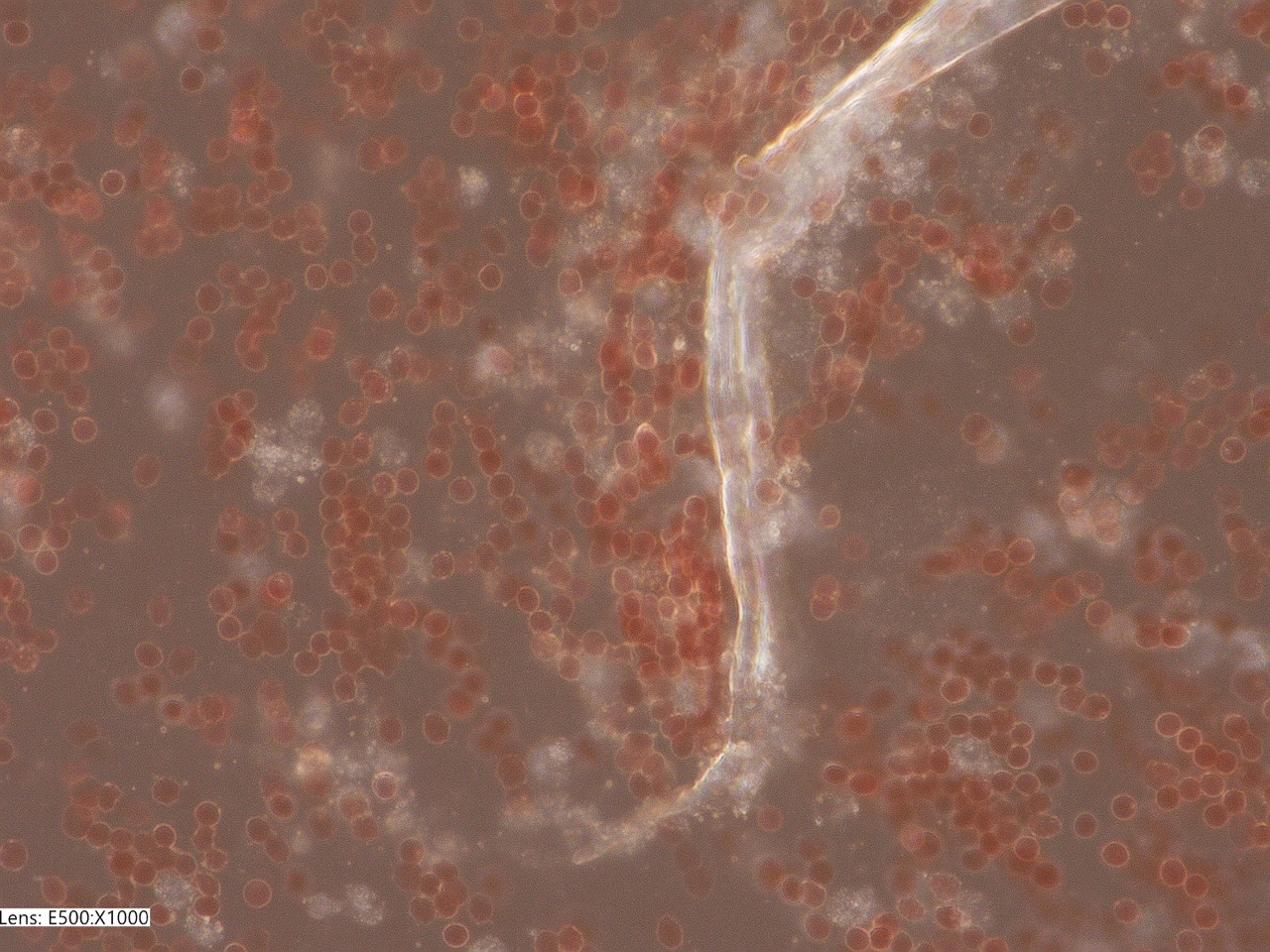

The vaginal microbiome is a mix of several microorganisms that live in symbiosis and help our body in a lot of biological functions.

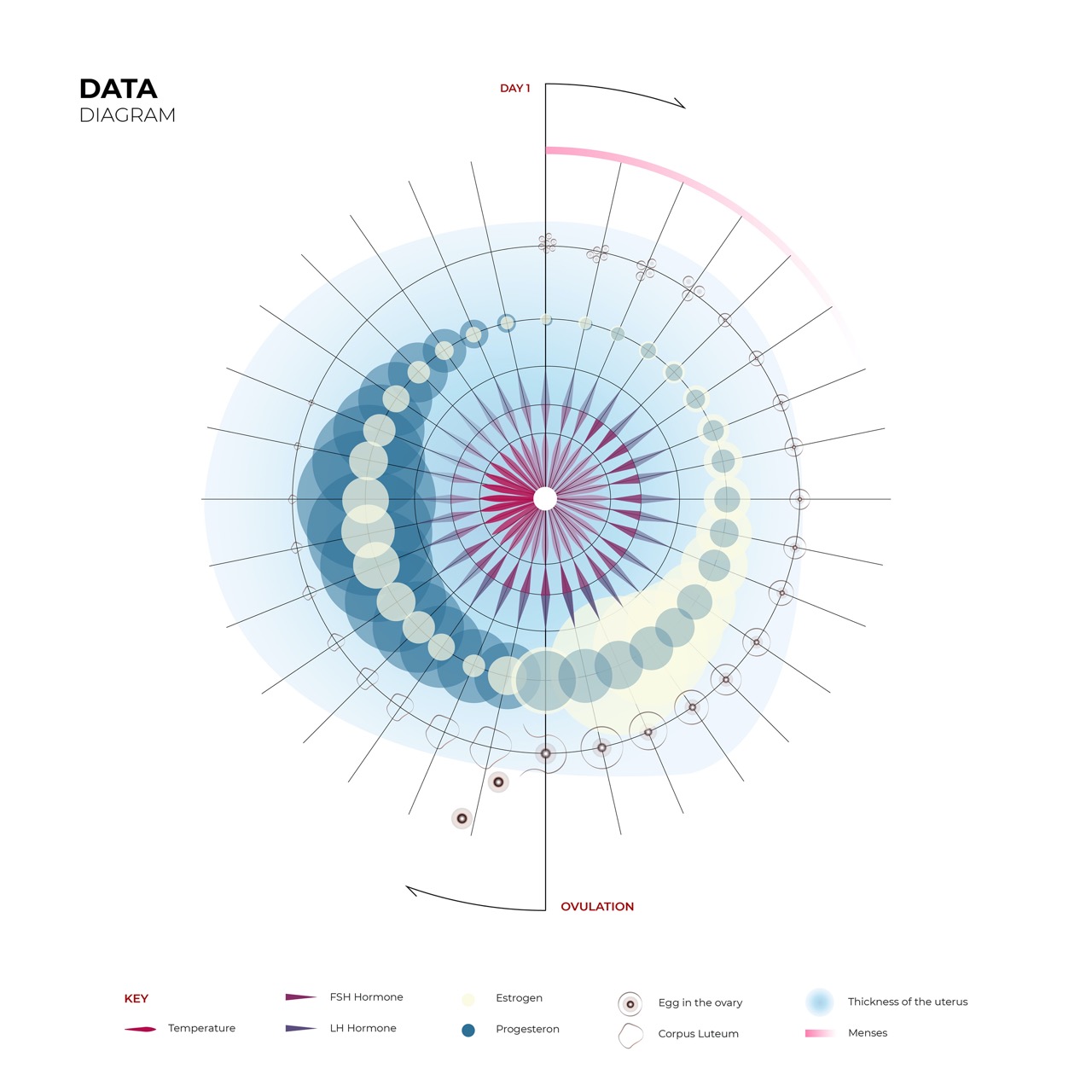

When I started my research, I discovered that, contrary to popular belief, most mammals do not menstruate. In fact, it is a feature exclusive to four species on the planet. In the human species, the fetus has access to its mother’s blood supply and it can control the hormones and consequently both blood sugar and pressure. That is where the endometrium comes in. To “protect” the mother’s body from embryo implantation, the endometrium gets thicker. After every ovulation that did not result in a healthy pregnancy, the superficial endometrium is expelled and we experience menses. However, this positive feature of the human species was mostly misconsidered all over history, referring to periods and blood as something impure, toxic, and dangerous.

The current menstrual hygiene products are extremely pollutant for the environment and the human body because of the chemical compounds embedded. While long-term products are made of synthetic materials, the most “natural” single-use products rely on the unsustainable consumption of resources. Moreover, the missing alternatives for managing menstrual cramps have led people to decide to chemically prevent periods using hormones, causing a chain effect on both the environment and the biodiversity. Therefore, these products have shaped the behavior of many generations by promoting silent and discrete single-use products equipped with applicators to not touch genitals and blood and to give the idea that a period was best to keep it secret.

Interestingly, I found that the first menstrual cup was invented a few years later than the first tampon, but it was unpopular until ten years ago, because not in line with our “periods-afraid” culture. However, it is the best product we have designed for period management because, instead of absorbing, it collects the blood, avoiding the exponential growth of pathogens that can affect the stability of the microbiome. The vaginal microbiome is a mix of several microorganisms that live in symbiosis and help our body in a lot of biological functions. It can be affected by the age, our diet, lifestyle, the products that we use and it also changes according to the different menstrual cycle phases because of the hormones, sugar content and blood alkalinity.

Can we imagine a future where menstruators can use products able to interact with this extremely complex micro-environment?

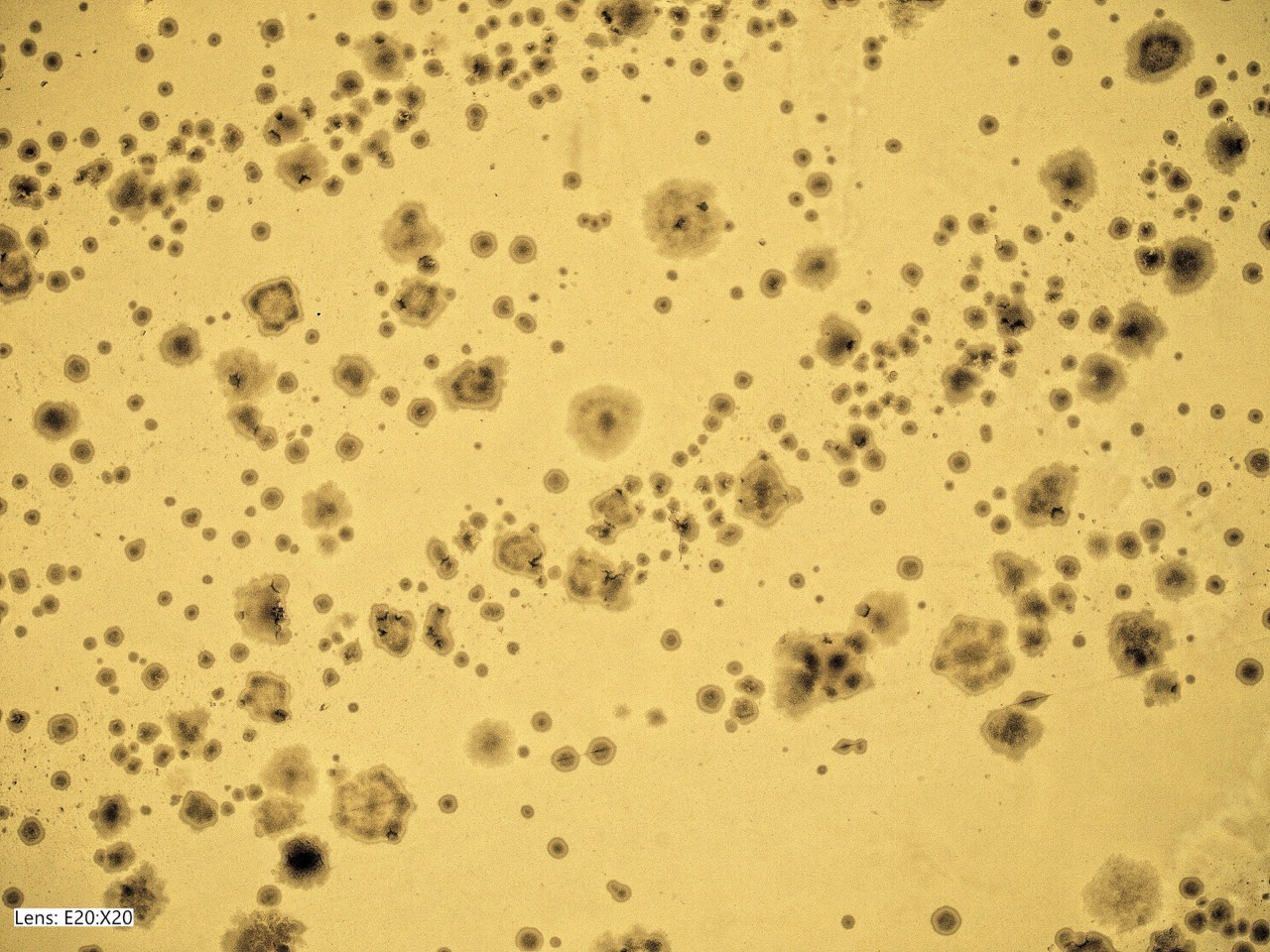

However, recent studies have found that it plays a very important role not only in fertility, pregnancy, and vaginal infections but also in dysmenorrhea symptoms, and severe menstrual cramps that affect around the 80% of menstruators. Scientists discovered that people with dysmenorrhea have a different microbial profile compared to people with less heavy periods. Lactobacillus as probiotic bacteria can produce anti-inflammatory compounds that help with menstrual cramps. Experiments show how these bacteria can both reduce the pain, and the number of painkillers used every month. Here is the main idea: can we imagine a future where menstruators can use products able to interact with this extremely complex micro-environment?

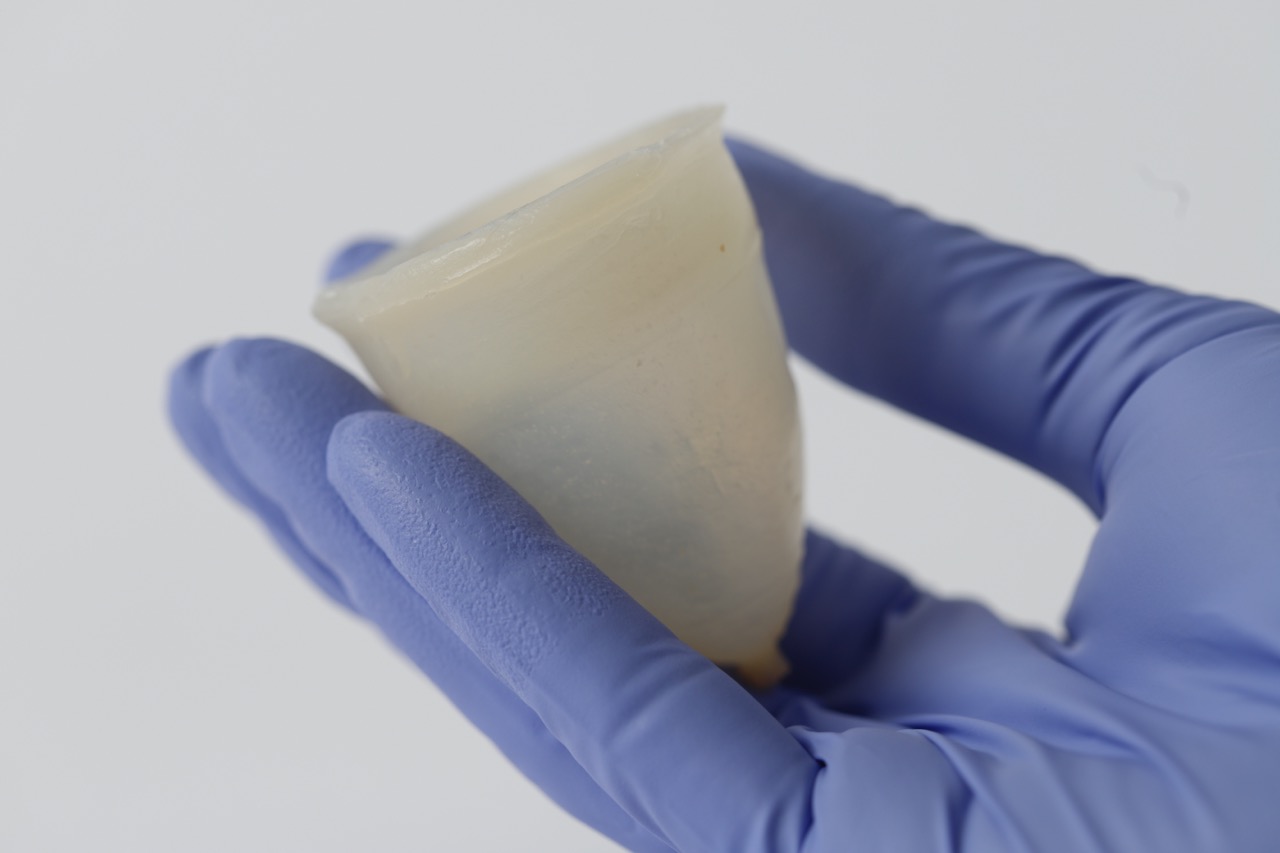

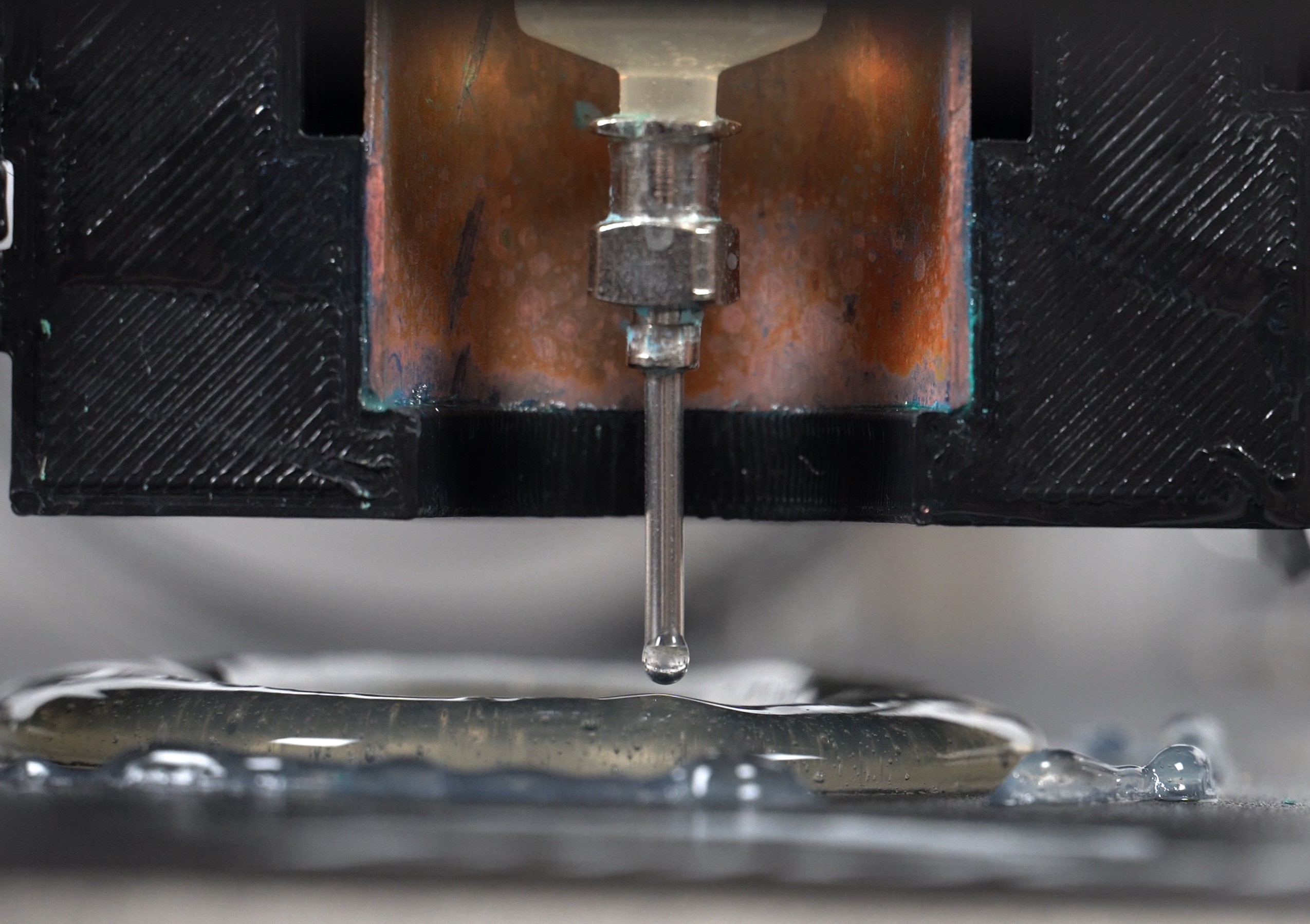

For this project, I have decided to explore hydrogels as suitable materials able to interact with the vaginal environment. These materials can act as a membrane while maintaining the structure, particularly interesting for their ability to absorb and release compounds. Due to their biocompatibility, they have aroused interest in biomedical industries to be applied in tissue engineering and drug delivery. After analyzing several peer reviews on these materials, sodium alginate was the most popular naturally derived hydrogel, so I have decided to mix it with a selective media for lactobacillus and test the best combination to achieve good flexibility and elasticity.

I was interested in using a digital fabrication tool because I believe it plays a key role to scale up the process and customizing medical devices able to be worn internally and adapt to different body shapes. I have decided to hack my 3D printer following an open-source tutorial to transform it into a bioprinter able to extrude hydrogels through a sterile syringe. The big challenge for me was to find a hydrogel able to self-sustain during the bioprinting process. Unfortunately, bioprinting is still a new process and finding a clear protocol to follow was quite difficult.

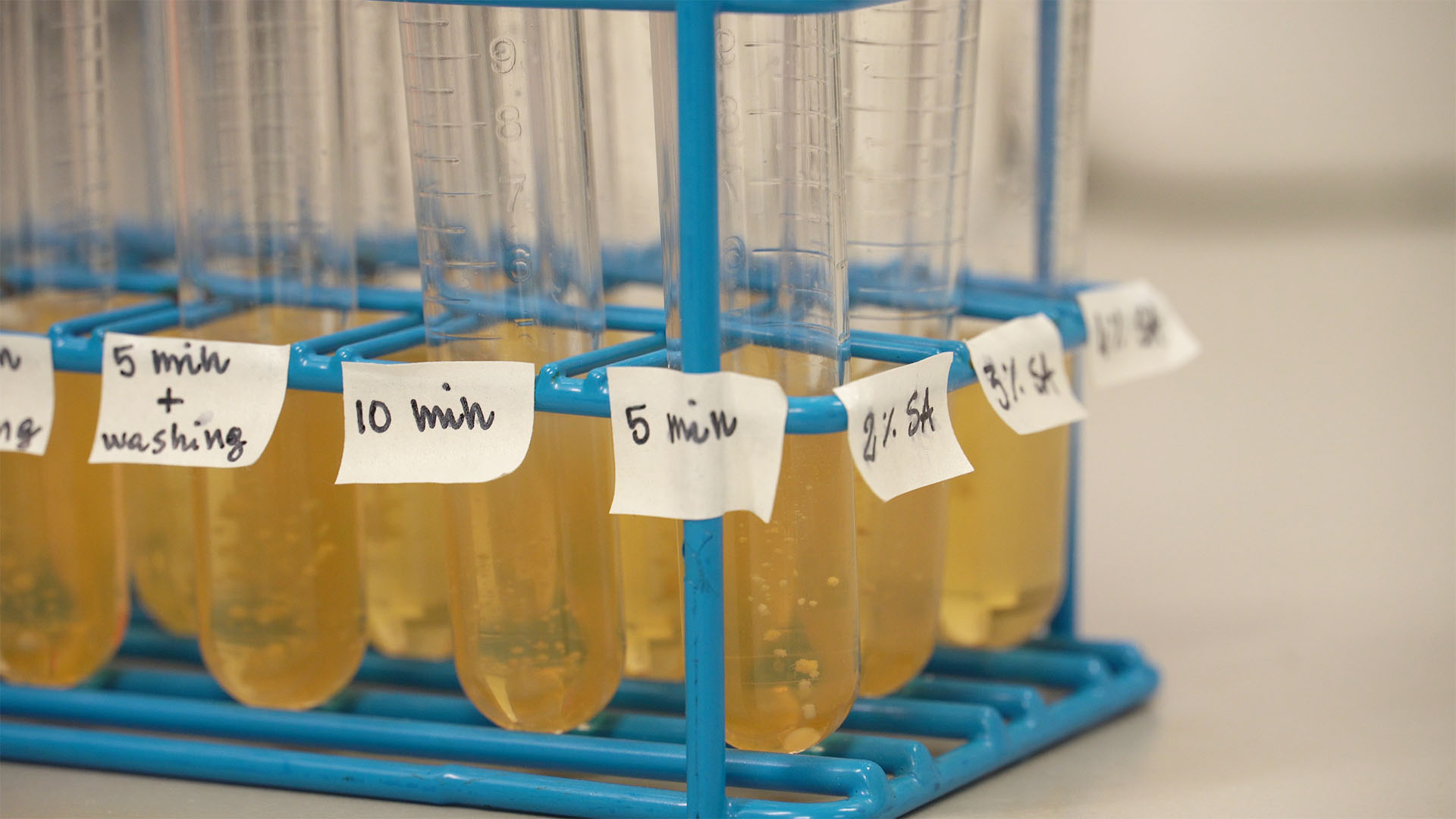

As an alternative, I have decided to cast my prototypes and the optimal result was achieved using a mould made of calcium chloride and agar to allow the alginate gel to become solid after a few hours inside the two parts mould. The lab experiments validated the project by answering questions like: are lactobacillus able to move, grow, and survive a cross-linked hydrogel? The first living menstrual cup prototype is made using a biocompatible hydrogel that allows bacterial viability. Several strains of vaginal lactobacillus extracted from my own body exponentially grew inside the material over two days of incubation at 37°C.

Further developments may lead to transforming it into the first “living” menstrual hygiene product present on the market.

Despite having decided to categorize it as a speculative project, further developments may lead to transforming it into the first “living” menstrual hygiene product present on the market. I believe that creating a stronger relationship with such an intimate object as a menstrual cup can allow menstruators to become more conscious about their bodies. Moreover, I think the most important feature is having a meaningful object able to overcome some stigma related to menstruations. With this project, I want to produce a shift between the production of single-use period products to be ashamed of and a beautiful product able to be exhibited in the home environment as part of the furniture.

Once a month, different strains of probiotic bacteria can grow and colonize the menstrual cup inside an incubator that biomimics the vaginal environment. The incubator is equipped with a touch screen that helps the user to navigate its functions. The screen interface is divided into three main sections: two of them to switch between “off-menses mode” (the care) and “on-menses mode” (the growth). The last one (the ritual) offers an overview of the process of listening to the body’s signals and understanding when it is time to start cultivating the bacteria. The cup can be used as usual during menses and, when off-menses, the care section can guide the user to keep the perfect “ground” to cultivate lactobacillus the following month and keep the living cup hydrated.

Share your thoughts and join the technology debate!

Be the first to comment