With the birth of agriculture, 10,000 years ago, humans entered into a mutually beneficial relationship with plants: the plants we chose to grow gave up their natural defenses, such as tough or bitter leaves, making them more tender and sweet. In turn, we cultivated and protected them. They became human nature. Today, tens of thousands of edible plant species can still be found, but we grow just a small fraction of them. We rely on just three species (rice, wheat and corn) to provide most of our food. There is a huge diversity of delicious plants, many of which are forgotten and on the verge of extinction. Uli Westphal's Seed Series is an ongoing attempt to document the seeds of all edible plants, one seed at a time.

Ruben Baart: Your work strongly focuses on food. Where does this interest come from?

Uli Westphal: While studying art in the Netherlands I got my groceries from a biweekly street market. At that time, these fruits and vegetables were my idea of natural produce. But most of it was grown not on a field but on mineral substrate in industrial greenhouses.

When I moved to Berlin I continued sourcing food from street markets, but the produce there looked different. Vendors would often sell fruits and vegetables that were rejected by distribution hubs catering to supermarket chains, or that came straight from small scale farms and didn’t undergo an aesthetic selection process in the first place.

I was fascinated by the diversity of shapes and colors of the produce that was sold here. They had beautiful sculptural qualities, but they also instantly triggered questions: Why is it that we would never see these kinds of fruits and vegetables in supermarkets? Are they natural, and if so, what mechanisms and reasons prevent them from entering the regular food markets? This encounter has influenced my work as an artist ever since.

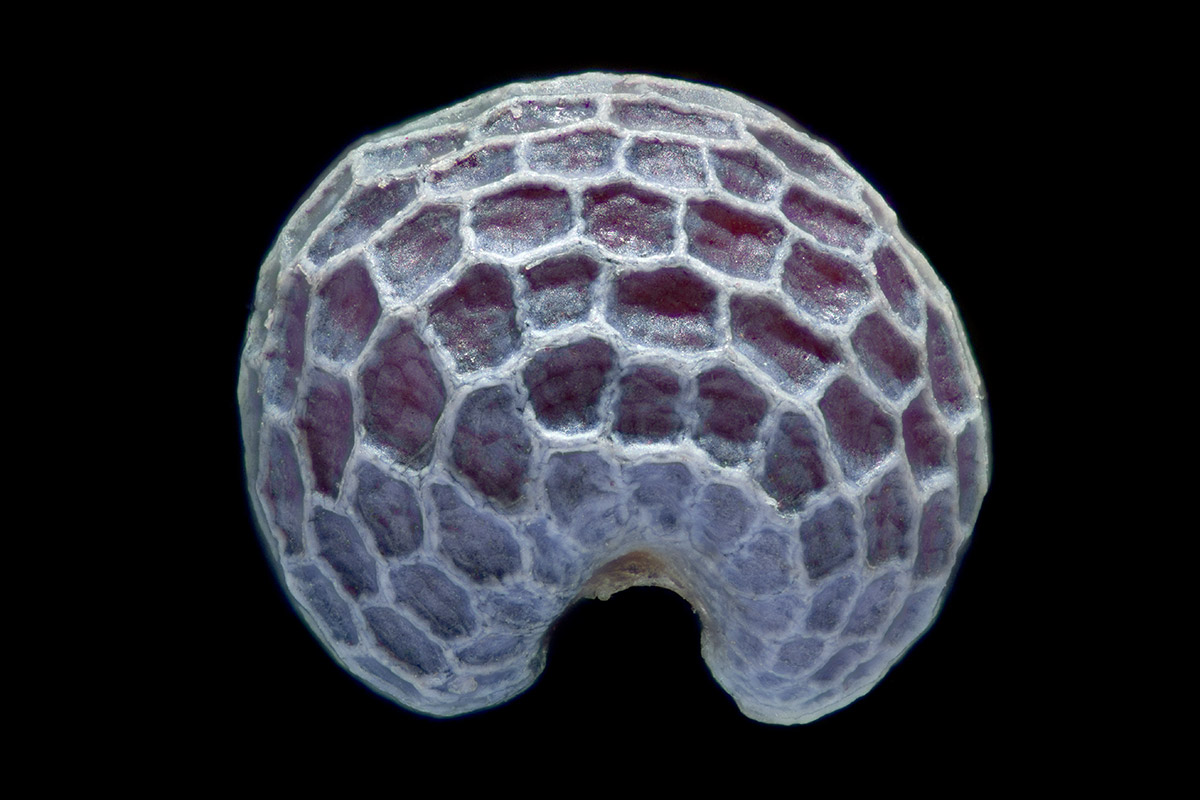

Uli Westphal, Seeds Series (2020-ongoing), Calendula officinalis — marigold

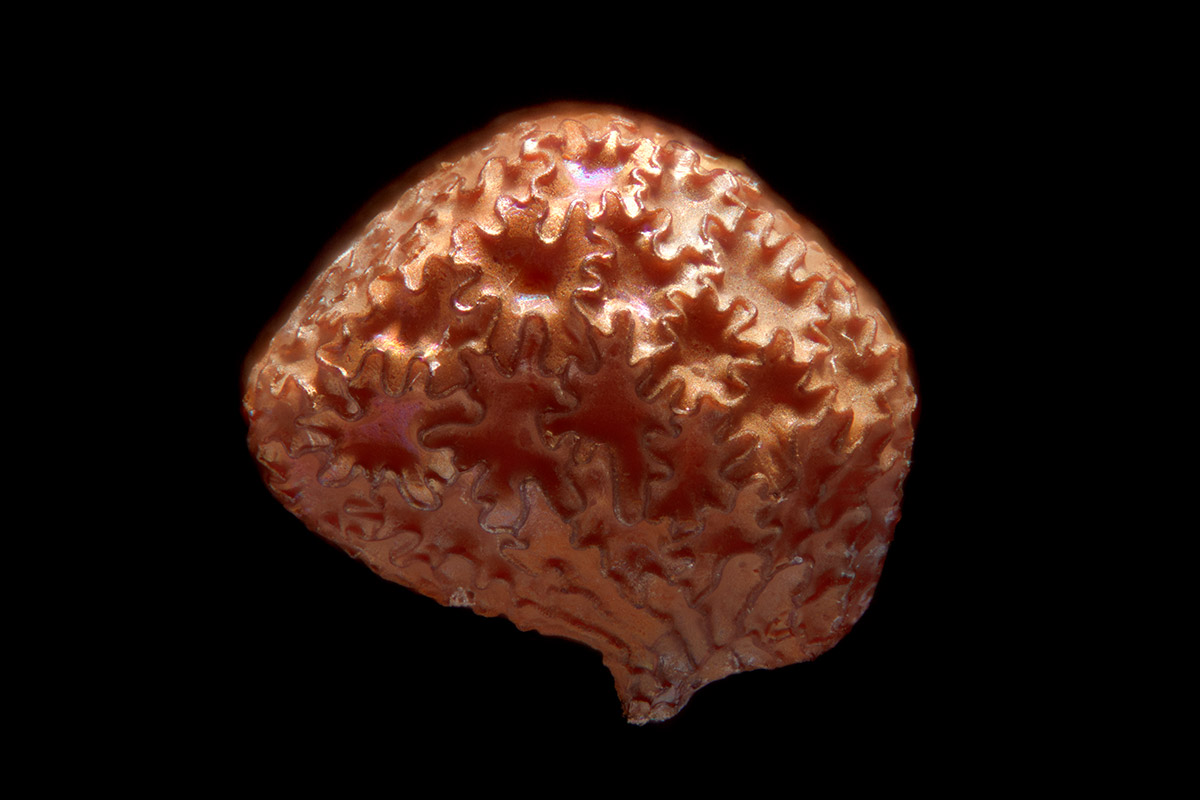

Uli Westphal, Seeds Series (2020-ongoing), Solanum lycopersicum — tomato

RB: What does it mean for you to work with food as a topic?

UW: My work has always been about the relationship between humans and nature. Food connects it all. It ties together so many topics and aspects of the human condition, the history of civilization, the transformation of our planet's ecosystems, along with the multi-sensory experience of food, its textures, smells, colors and flavors.

From an evolutionary perspective, crop plants are an intersection between humans and nature: when we started farming, 10000 years ago, we entered into a symbiotic relationship with plants. The plants we chose to grow gave up their natural defenses, such as bitter leaves or tough seeds to become more palatable for humans. They became more tender, sweeter, juicier. In turn we cultivated and protected them. They became human nature.

Over the course of history we have developed a seemingly infinite diversity of shapes and colors from the wild ancestors of today's domesticated plants. Our planet still harbors tens of thousands of edible plant species, but today we grow just a tiny fraction of them. There is a tremendous diversity of delicious plants out there which are forgotten, underutilized and often on the brink of extinction. We need to raise awareness, celebrate and safeguard this botanic cornucopia.

From an evolutionary perspective, crop plants are an intersection between humans and nature: when we started farming, 10,000 years ago, we entered into a symbiotic relationship with plants.

Uli Westphal, Seeds Series (2020-ongoing), Centaurea cyanus — cornflower

Uli Westphal, Seeds Series (2020-ongoing), Paiflora quadrangularis — giant granadilla

RB: What do you want people to experience when they encounter your work?

UW: I'm always looking for a shift in perspective. Think of a tomato. It’s so common that we don't really pay attention to it, it has become a mundane object. But if you see it in a different shape or in a different stage of its life, for example, in the form of a seed, you hardly recognize it anymore. In that little moment of estrangement you can see something in a new light and start reflecting on it.

For my latest project, the Seed Series, I take highly magnified photographs of crop plant seeds. Even when the seeds come from very common fruits and vegetables, they appear alien at first sight.

Uli Westphal, Seeds Series (2020-ongoing), Papaver somniferum — bread seed poppy

Uli Westphal, Seeds Series (2020-ongoing), Fagopyrum esculentum — buckwheat

RB: How did the Seeds Series come about?

UW: During the COVID19 pandemic, I was confined to my studio: I couldn't travel anymore and I had to work with what was around me. By then I had collected many different seeds from all over the world. I learned how to use microscopic lenses to photograph the seeds and build a machine to help me.

It's a complicated process: it’s not just one photograph, but rather built up from often hundreds of images that are needed to bring the whole seed into focus. It took me a while to master that.

The Seed Series is a logical continuation of my ongoing work to document the earth's crop diversity. I started by photographing individual fruits and vegetables, then all the cultivated varieties of single crop species and for this new series I attempt to photograph the seeds of all edible plants, one per species.

I have a shortlist of 3000 plant species that are rated highly edible, and tens of thousands other potential candidates. I'm currently at 400. It’s a never-ending project and that’s a wonderful thing.

I have a shortlist of 3000 plant species that are rated highly edible, and tens of thousands other potential candidates. I'm currently at 400. It’s a never-ending project and that’s a wonderful thing.

Uli Westphal, Seeds Series (2020-ongoing), Rose spp. — rose hip

Uli Westphal, Seeds Series (2020-ongoing), Goypium herbaceum — levant cotton

RB: This summer the European Union has voted to be more lenient to the use of GMOs (Genetically Modified Organisms). What is your stance on this?

UW: Since the beginning of agriculture we have actively shaped plants and animals to fit our needs. But this history of domestication is something fundamentally different than the recent advances in genetic engineering.

Domestication of plants and animals has been a slow process that took shape over Millennia, driven by millions of farmers, utilizing mechanisms that already existed in nature, and moving at a pace that was slow enough for ecosystems and societies to adapt.

Gene editing techniques are evolving at a rapid speed, out-pacing public awareness, debate and regulation, and have the potential to alter life in ways that are unprecedented. Genes are the core of self replicating organisms, which, once released into the wild, can be impossible to contain.

Since the beginning of agriculture we have actively shaped plants and animals to fit our needs.

Genes are incredibly complex. Even if we could fully understand what effect changes to its gene will have on an organism, it is impossible to predict how this organism will affect its even more complex environment. The environmental impact might be unintended or deliberate: Gene drives can for example render an organism to produce only male offspring and thus killing off an entire species over a few generations once released. But these are hypothetical concerns until something goes wrong.

What we can clearly see already, since the introduction of GMOs, is that they are most of all a means of control. They allow corporations to design plants that are dependent on specific agrochemicals, which are sold together with the seeds. And they allow them to patent plants, taking away farmers rights to save their own seeds from a year's harvest.

On-farm seed production was always the driving force for crop diversity and a means for farmers to stay independent and self-sustaining. Try growing non-proprietary corn amidst an ocean of GMO corn. Your plants will cross-pollinate with GMOs and when you replant your seeds you can get sued for violating patent rights. To illustrate the power of these companies: In 2020 only four firms controlled approximately 51 percent of global seed and more than 62 percent of agrochemical sales.*

I'm not opposed to fundamental research in genetics, but I'm opposed to rushing towards genetic engineering as a design tool and technological quick fix, especially when it comes to food production.

* Howard, Philip, 2023, Recent Changes in the Global Seed Industry and Digital Agriculture Industries

I'm not opposed to fundamental research in genetics, but I'm opposed to rushing towards genetic engineering as a design tool and technological quick fix, especially when it comes to food production.

Uli Westphal, Seeds Series (2020-ongoing), Ribes rubrum — redcurrant

Uli Westphal, Seeds Series (2020-ongoing), Pastinaca sativa — parsnip

RB: But the industrial approach to edible crops also helps more people around the world to have access to food?

UW: The world already produces more food than all of us can eat. Still people go hungry. Currently it is more a problem of waste and distribution, not production. I doubt that centralized production by industrialized countries can feed the world.

We need millions of farms producing food locally where it is needed. And these farms should be equipped with the newest technology as long as it is non-destructive, sustainable, helps the farmers and doesn't become an unbearable financial burden for them.

I believe there are many solutions already existing in nature, and that some technologies are nonsense, a weird result of our human tendency to separate ourselves from nature.

For example, all plants use photosynthesis. They are in fact living solar panels. If you can grow them under the sun, why then would you put them in a dark room and shine LED lights on them? It's a fascinating philosophical idea somehow that we grow them apart from nature in a building or in a lab. Maybe in space it would make sense. But I think that extra-orbital human spaceflight is also nonsense, as long as we haven't figured out how to do things right on earth.

I believe there are many solutions already existing in nature, and that some technologies are nonsense, a weird result of our human tendency to separate ourselves from nature.

Uli Westphal, Seeds Series (2020-ongoing), Phaseolus vulgaris — common bean

Uli Westphal, Seeds Series (2020-ongoing), Actinidia deliciosa — kiwi

RB: One of our core slogans is going forward to nature, which means using technology for a more natural world. How in your opinion, may we go forward to nature?

UW: The fundamental difference between what nature creates versus what humans create, is the speed and scope of change that comes with it. Apart from cataclysmic events like volcanic eruptions or meteor impacts, ‘old nature’ has evolved slowly and subtly, allowing for ecosystems to stabilize while transitioning into ever new forms. The speed at which it evolves makes our new next nature cataclysmic as well, and we need to be extremely careful that we don't override the old with the new.

Destructive as we humans are, we are also capable of creating dense and complex fractal landscapes, full of niches and edges that can harbor biodiversity. Cities are a great example of this, often the biodiversity found here is bigger than that of the surrounding countryside. If we create complexity like this in agriculture as well, we can actually support biodiversity.

Rather than being mono-cultural deserts, our farms could be thriving, self perpetuating ecosystems. But this means we have to allow old nature to be part of our next nature, and give it time and space to adapt.

Rather than being mono-cultural deserts, our farms could be thriving, self perpetuating ecosystems.

Uli Westphal, Seeds Series (2020-ongoing), Nicotiana tabacum — tobacco

Uli Westphal, Seeds Series (2020-ongoing), Malva alcea — hollybook mallow

This interview was conducted as part of the exhibition Spacefarming, which is currently on display at the Next Nature Evoluon in Eindhoven. Spacefarming explores how we can grow our food differently in the future, or even on other planets.